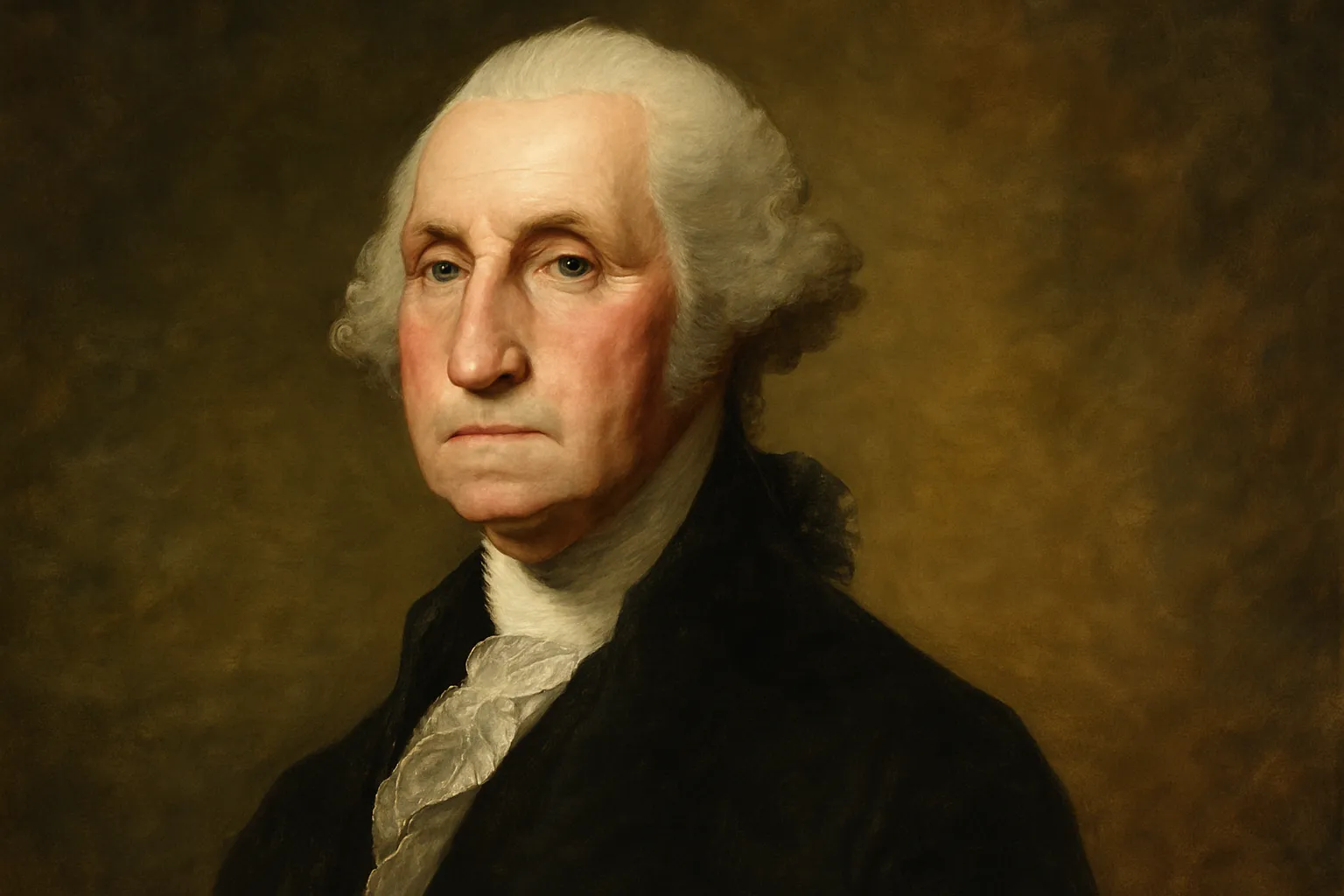

Biography of George Washington: The Founding Father Who Built a Nation

Few figures loom as large in American history as George Washington. Soldier, statesman, and the nation’s first president, he symbolizes the birth of the United States. But behind the marble statues and dollar bills lies a deeply human story—a man of ambition, self-restraint, and vision who navigated monumental challenges to forge a fragile union into an enduring republic. His path was not inevitable. It was carved with careful calculation, personal sacrifice, and an unwavering sense of duty.

This is the life of the man history would come to call the “Father of His Country.”

From Surveyor to Soldier (1732–1753)

George Washington was born on February 22, 1732, in Westmoreland County, Virginia, into a respected, though not aristocratic, family. His father, Augustine Washington, was a successful planter, while his mother, Mary Ball Washington, was known for her strict discipline.

When George was just 11, his father died, leaving him without access to the higher education that his older brothers received in England. Instead, he gained a practical education, learning arithmetic, surveying, geography, and moral philosophy—knowledge that would serve him far beyond the classroom.

At 17, Washington earned his credentials as a professional surveyor, mapping vast tracts of Virginia’s frontier. These years in the wilderness not only toughened him physically but also planted the seeds of his strategic mind, disciplined temperament, and lifelong connection to the land.

The French and Indian War (1754–1763)

Washington’s first taste of leadership came during the French and Indian War, part of the broader conflict between Britain and France for control of North America.

In 1754, he led a small expedition to confront French forces in the contested Ohio Valley. The ensuing skirmish at Fort Necessity ended in a stinging defeat. Though embarrassed, Washington’s composure under pressure earned him attention.

A year later, as an aide to British General Edward Braddock, Washington witnessed a disastrous ambush where Braddock was killed. Amid chaos, Washington rallied survivors, his courage solidifying his reputation as a rising colonial leader.

Though still young, Washington absorbed critical military lessons—the value of preparation, the danger of overconfidence, and the importance of adaptability—qualities that would later define his leadership during America’s fight for independence.

Landowner, Family Man, and Public Figure (1759–1774)

In 1759, Washington married Martha Custis, a wealthy widow. This union elevated his social standing and expanded his holdings, including the sprawling Mount Vernon estate. There, Washington managed a large plantation, overseeing crops like tobacco and wheat—while tragically relying on enslaved labor, a contradiction that would shadow his otherwise principled life.

Beyond his role as planter, Washington entered politics, winning election to the Virginia House of Burgesses. Although initially moderate in his views, Britain’s escalating taxation policies and trade restrictions gradually radicalized him.

Like many colonists, Washington resented what he saw as Parliament’s disregard for American rights. But even as tensions grew, few could have foreseen how deeply he would eventually shape the revolution to come.

The American Revolution: Commander of the Continental Army (1775–1783)

When open conflict erupted at Lexington and Concord in 1775, the Second Continental Congress named Washington Commander-in-Chief of the fledgling Continental Army. His selection balanced regional interests—he was a Virginian leading primarily New England troops—and capitalized on his growing reputation for resolve and integrity.

Washington faced monumental challenges:

-

A poorly trained and ill-equipped militia.

-

Chronic shortages of money, food, and weapons.

-

Political infighting and wavering public support.

-

A superior British army with vast resources.

Early defeats, including the disastrous defense of New York (1776), tested his resolve. Yet he refused to crumble. His bold crossing of the Delaware River on Christmas night, 1776, and subsequent victories at Trenton and Princeton, reignited American morale.

Perhaps Washington’s greatest triumph was his leadership during the bitter winter at Valley Forge (1777–1778), where he kept his army intact against near starvation and despair. His recruitment of Baron von Steuben to instill discipline and professionalism into his ranks would prove decisive.

The war’s turning point came with the Franco-American alliance, secured largely through Washington’s steady hand. Finally, at Yorktown (1781), with the support of French forces, Washington orchestrated the British surrender, ending major combat operations.

The Most Remarkable Act: Surrendering Power (1783)

With victory secured, Washington did something revolutionary—he voluntarily relinquished his military authority and returned to Mount Vernon. In an age when victorious generals often seized power, his decision stunned the world and established an enduring precedent for civilian rule.

King George III reportedly remarked that if Washington truly gave up power, “he would be the greatest man in the world.”

Architect of the Constitution and First Presidency (1787–1797)

The fragile new republic, governed under the ineffective Articles of Confederation, quickly found itself in crisis. In 1787, Washington was summoned to preside over the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia. His presence lent legitimacy to the difficult task of creating a stronger federal government.

With the Constitution ratified, Washington was unanimously elected the first President of the United States in 1789—a post he reluctantly accepted out of a renewed sense of duty.

As president, Washington navigated uncharted waters:

-

He formed the first executive cabinet, balancing competing views from figures like Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson.

-

He established fiscal stability through the creation of a national bank.

-

He enforced federal authority during the Whiskey Rebellion (1794), proving the government’s ability to maintain order.

-

He maintained neutrality amid rising tensions between Britain and revolutionary France, steering clear of foreign entanglements.

Washington’s restrained approach to power set vital precedents—he refused grand titles, emphasized rule of law, and modeled executive modesty, ensuring the office served the republic rather than dominating it.

The Farewell Address and Lasting Warnings (1796)

After two terms, Washington chose to step down in 1796, again declining power when many hoped he would stay indefinitely. In his famous Farewell Address, he offered prescient warnings:

-

Beware of partisan divisions.

-

Avoid foreign entanglements.

-

Protect the Union from regional conflicts.

-

Guard against excessive public debt.

Generations of leaders have cited his words as both wisdom and prophecy, echoing his vision for a unified, cautious, and self-reliant republic.

Final Years and Death (1797–1799)

Retiring to Mount Vernon, Washington dedicated his final years to his estate. Yet even in retirement, he remained vigilant. In 1798, amid rising tensions with France, President John Adams called him to once again command a provisional army—though war was ultimately averted.

In December 1799, Washington contracted a severe throat infection following prolonged exposure to cold and rain. He died on December 14, 1799, at the age of 67.

His death plunged the nation into mourning. Across political lines, Americans recognized him as the towering figure who held the fragile experiment of republicanism together.

Controversies and Contradictions

Though universally revered, Washington’s legacy includes complexities that continue to spark debate:

-

Slavery: As a plantation owner, Washington enslaved over 300 people. Only late in life did he begin to question slavery’s morality. In his will, he arranged for the emancipation of his slaves after his wife’s death—a rare step among the Founders.

-

Native American relations: His expansionist policies led to the dispossession and displacement of many indigenous peoples.

-

The cult of personality: Despite his resistance to monarchy, Washington quickly became an object of near-mythical reverence—a paradox he himself tried to avoid.

Modern historians continue to wrestle with these contradictions, painting a fuller picture of both Washington the icon and Washington the man.

George Washington in American Memory

Washington’s image has become deeply ingrained in American identity:

-

His face adorns the U.S. dollar bill, coins, and postage stamps.

-

The monumental Washington Monument in the nation’s capital honors his legacy.

-

The city of Washington D.C. bears his name as the permanent seat of government.

Beyond monuments, Washington lives on in classrooms, films, novels, documentaries, and public discourse. He remains an enduring symbol of selfless leadership, republican virtue, and the possibilities of democratic governance.

George Washington was neither a fiery revolutionary nor a radical philosopher. His greatness lay in his strength of character, his ability to balance ambition with restraint, and his unwavering sense of civic responsibility.

He won a war that many thought unwinnable, led a divided nation through its fragile infancy, and voluntarily stepped away from power—twice. In doing so, Washington not only forged a nation but defined the very essence of republican leadership.

More than 200 years after his death, Washington remains a timeless example of principled leadership—reminding us that true greatness often lies not in seizing power, but in knowing when to give it up.