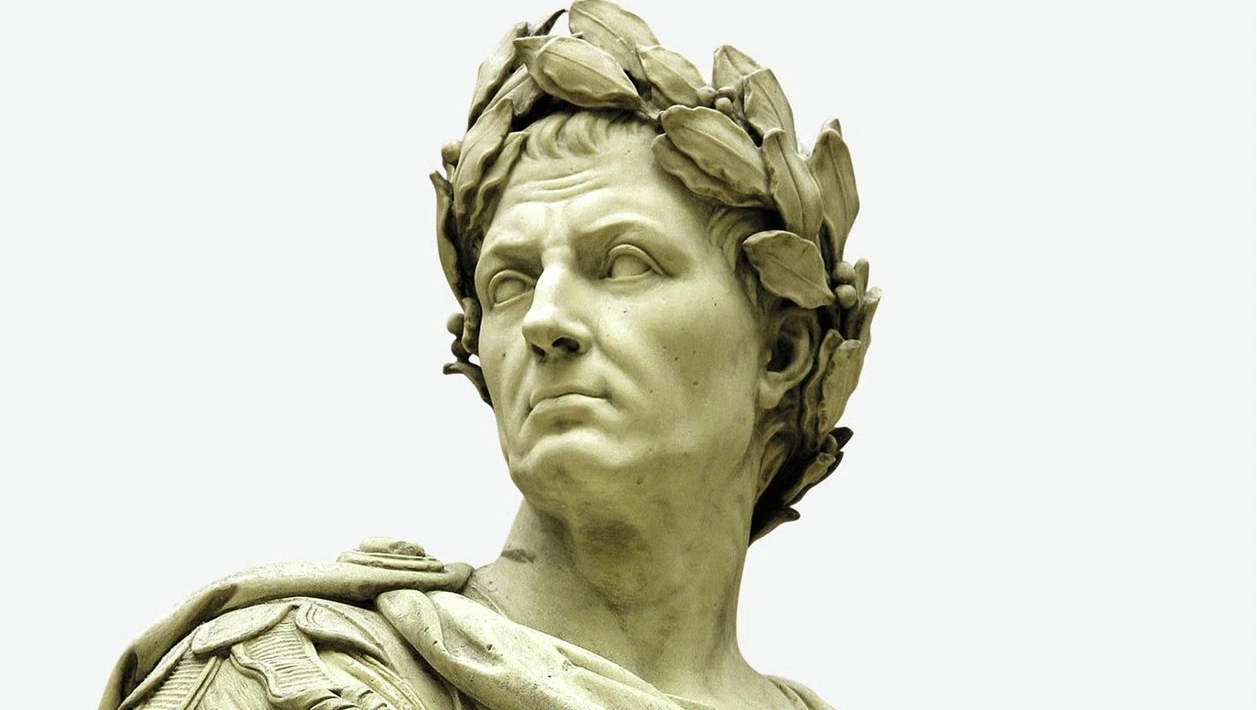

Julius Caesar (100 BC-44 BC)

The transition from the Republic to the Roman Empire had as its main protagonist one of the most famous figures of antiquity, whose fame continues to this day: Julius Caesar (100-44 BC). He was exceptionally gifted as a strategist, politician, orator, and prose writer. His political and military career, after leading the victorious Gallic wars and defeating Pompey in the Civil War (49-46), led him to impose himself on the weak republican institutions and take absolute control of power, from where he set out to carry out reforms that would enable Rome to maintain its growing influence in the Mediterranean. The conspiracy that ended his life two years later prevented him from seeing his plans realized, but the man he appointed as his successor, Octavian Augustus, would eventually become the first Roman emperor.

Gaius Julius Caesar was born on July 13, 100 BC (according to the most common date) in a non-aristocratic neighborhood of Rome, near the present-day Via Cavour. Little is known about his childhood, which was spent in an aristocratic family, the Gaius Julia family, which claimed descent from Aeneas (who was considered the son of Venus), to which at some point a branch was added that added the name Caesar. Members of the family lived on the fringes of the constant struggle for positions that would allow them access to public office until they reached the consulate, their highest aspiration.

Childhood and early youth were short in those days. From the age of ten, Caesar was placed in the care of a brilliant teacher specializing in Greek and Roman literature, Marcus Antonius Gnifton, to educate him. His natural talents allowed him to make the most of his teacher’s teachings, mastering his language and learning the basics of rhetoric, essential for a political career.

Although his family did not hold high office, his communal tendencies led him to the Popular Party. Julia, Caesar’s father’s sister, had married Gaius Marius, a commoner by birth but a very powerful man because of his military ability. The family, perhaps through Marius, entered the circles of the Popular Party. Julius Caesar’s father could do nothing less than hold the second most important position in the state, that of praetor. He held this position when his fifteen-year-old son was forced to attend the ceremony in which he gave up his purple brocade child’s robe and was presented with a virile toga.

Caesar was fifteen years old, in 85, when his father, a man, died. He immediately took Cornelia, the daughter of Senna, one of the leading leaders of the popular party (along with Gaius Marius) and a man of power in Rome, as his wife. With this decision, Julia’ s gender ended up being definitively linked to the interests of the people against the corrupt Roman aristocracy. All of this must have been somewhat difficult for Julius Caesar, who was a young man living a prejudice-free life, already free from his master’s strictness and inclined towards all kinds of reading, including theater.

In order to marry Cornelia, he had to break a previous engagement, which caused tensions within the family. At the beginning of his married life, Caesar must have entered the circle of important men who surrounded his aunt Julia, who was the widow of Marius.

In 82, the Roman consul and general Sulla (who had defeated Mithridates and driven him to the borders of his primitive kingdom in Pontus) returned triumphantly to Rome and, as usual, took full revenge on his “popular” opponents; He assassinated them, barred their descendants from public office, seized their property, and established a new form of state, inaugurating a kind of indefinite absolute dictatorship, a legal concept that Julius Caesar would not forget in the future. But for now, Sulla, who had some regard for aristocratic families with a penchant for populism, demanded that Caesar disown Cornelia. Caesar responded to Sulla’s messenger with a famous phrase (“Tell your master that Caesar commands only Caesar”) and opted for exile in Asia.

This was not easy; Caesar was persecuted and had a price on his head. He had to buy his freedom from one of the soldiers who found him, and finally, at the entreaties of the dictator’s close relatives and the intercession of the priestesses of the goddess Vesta, Sulla pardoned the “young man with the loose garment,” a nickname referring to Caesar’s habit of not adjusting the belt of his dress, which fell freely, in accordance with a custom then considered unmanly. It was a reluctant pardon. Sulla had hinted at the boy’s fearsome future when he said, according to Suetonius, that Caesar was a polymarius enesi (there are many Marys in Caesar), referring to the danger inherent in his assertive personality. However, Caesar did not hurry back to Rome and went into the service of Praetor Termes, who gave him the rank of officer, because Caesar was the son of a senator. Thus he participated in the capture of Mytilene on Lesbos, a city allied with Mithridates, and his military performance earned him a medal.

So Termes decided to send him to the court of King Nicomedes IV of Bithynia (a kingdom on the southern shores of the Black and Sea of Marmara) to strengthen their relationship. It was rumoured at the time that a close friendship had developed between Nicomedes and Caesar. In fact, Caesar returned to Bithynia several times, and after the death of Nicomedes, the kingdom was incorporated into Rome as another province and all the inhabitants became Caesar’s “clients”. This happened in 74 B.C. By this time Caesar was absolute dictator of Rome, and even in the midst of great celebrations (a curious example of the freedoms enjoyed by some people in Rome at this time) his own soldiers sang songs ridiculing him for his possible homosexual relationship with Nicomedes. His enemies often reminded him of this shameful episode and even gave him the infamous nickname Bithynicam reginam (Queen of Bithynia ).

Rise to power

After Sulla’s death, Caesar returned to Rome in 78. In his short life he had gained considerable experience in public affairs and developed his leadership skills. Caesar no doubt thought that Sulla’s death would enable him to make rapid progress in the Popular Party, but he was wrong. Sulla kept everything in order, and the conservative Optimates (“good men”) dominated the Senate and their power held the PP back. Julius Caesar, a natural politician (and to understand the significance of many of his actions, he must always be understood that way), began to deepen his understanding of the maze of public affairs. Finding his training incomplete, he went to Rhodes to study rhetoric under Apollonius of Molossa, a brilliant teacher who discovered in his pupil an innate eloquence. Among his contemporaries, only Cicero surpassed Apollonius in the art of oratory.

During his travels he was kidnapped by pirates who ravaged the Mediterranean and lived off the ransoms of their victims. The story is undoubtedly exaggerated, but the fear and respect with which he was treated by the pirates (as we have said) illustrates Caesar’s hubris and his ability to charm even his enemies. Having obtained his freedom, he gathered a small army, hired a ship, put to sea and attacked the pirates, defeating them and leaving him and his soldiers everything they had. The survivors of this adventure were eventually crucified in Miletus, and Caesar immediately launched an attack on Mithridates, who had again risen against the empire. At the time he was unaware of the will of Nicomedes IV, which was of great importance to him, since the king of Bithynia had left him a legacy which, together with the spoils of the pirates, restored his always precarious financial position.

The battle against Mithridates, however, was left to others, for the death of his uncle Aurelius Cota in 74 left a vacancy in the Roman Pontifical College. These appointments hastened Caesar’s political career, and in 68 he was appointed quaestor and went to Hispania Ulterior, where, it is said, he wept before the statue of Alexander the Great, erected in the city of Cadiz, thinking how small his career had been compared with that of the conqueror of the East, and how much he wished to emulate the invincible Macedonian general. He once dreamt that he raped his mother, which alarmed him, but the soothsayers foretold good things for him, as they explained that the mother symbolized the earth, the mother of all, which meant that he would conquer the world. In fact, over the next few years he amassed a dazzling number of honours: in 65 he was appointed prime minister, and in 63, when the president of the Pontifical Academy died, Caesar, aged 27, ran against the optimistic leader Catullus.

Caesar knew he was taking an economic risk (power struggles always require money) and that if he lost he would be ruthlessly persecuted. The election, however, showed the prestige he enjoyed among the people, and he was appointed pontifex maximus.62 In 62 he was sent as general counsel to the territory of Hispania Ulterior, which he already knew well, and there he not only built up solid friendships but also enriched the state finances (much to Rome’s satisfaction) and greatly increased his personal prowess and greatly strengthened his ability to command an army, which was essential to Rome’s political success. When he returned to the Eternal City in 60, the way was open for great adventures.

The Triumvirate and the Gallic Wars

In 59 he was given the highest post of consul. Realizing the power of the Senate (which was dominated by conservatives), Caesar skillfully disposed of his unfortunate relationship with the rebel Catiline, understanding that only an alliance between the powerful could neutralize the equal. He therefore suggested to his old friend and patron , Grassius, that he and Pompey form a common defensive organization so that they could act in unison (this organization became known as the “triumvirate”). The alliance was so effective that Caesar was appointed consul along with Calpurnius Bibulus (a would-be equerry).

Caesar’s daughter Julia married Pompey, further strengthening the triumvirate. Caesar in turn married Calpurnius.62 Caesar’s abandonment of his second wife Pompeia for adultery was marred by scandal: during a party to celebrate the Bona Dea mystery at Caesar’s home, a maid discovered an unwanted guest, Publius Clodius, disguised as a woman, and this incurred the wrath of those present. it was alleged that Pompeia was accused of being Clodius’s mistress, an accusation that could never be proven. Caesar, unwilling to believe the accusation, absolved both of them of adultery. Everyone was surprised that he still rejected his wife, but he responded with the famous phrase, “Caesar’s wives must not only be chaste, but appear chaste.”

Caesar’s progressive legislation was based on agriculture. He encouraged the passing of laws granting land to veterans and settling colonists in conquered lands, a practice that later spread throughout Italy, while granting full Roman citizenship to colonists. Unable to resist Caesar, Publius preferred to withdraw. The Plebeian tribune Publius Vatinius, an old friend and colleague of Caesar’s, in order to prevent Caesar from being tried by the conservatives after coming to power, proposed a law, which the senate could not disapprove, under which Caesar became president (which prevented his being tried later) and for a period of five years was given power over the three legions, the provinces of Gaul (Cisalpine and Transpadian Gaul) and the province of Illyria.56 These concessions were renewed for another five years by the “triumvirate” at a conference in Lucca in April 56.

Meanwhile, Crassus remained in Syria, waged war against the Parthians, and died in 53, while Pompey remained president of Spain. These conditions allowed Caesar to seize all power. To achieve this, any means were useful: he allowed Clodius, the former lover of his wife Pompey, to be adopted by the plebeians so that he could join the plebeian tribunes, although he was originally a nobleman. Thus the grateful Clodius began to rid Caesar of his enemies.

Caesar appears to have decided not to intervene in the Gallic war, but when the inhabitants of the province ask him to intervene, he does, and the Aeduians begin to feel threatened by the Helvetians, who are also seeking new territory, fuelled by the invasion of Germanic tribes led by Ariovistus. Caesar’s army came to the aid of the Aedui and defeated the Helvetians and Suebi. This marked the beginning of the systematic invasion of Gaul by Caesar’s army, assisted by his lieutenants Labienus and Crassus.

The battle was long, and the whole country was sacked, a third of the population killed in battle and another third probably sold into slavery. One after another, in a campaign in which Caesar was defeated, all the Gauls were conquered. In the midst of this struggle, Caesar landed in England between 55 and 54 and fought across the Thames, but was eventually forced to retreat. The following year (winter 54-53), Gaul was again in turmoil, with the Eburones and Trevians, and eventually all the Gallic tribes under Vercingetorix, rebelling. At the battle of Gergovia the Romans suffered, but Vercingetorix’s troops were besieged for a long time and finally defeated at Alesia. The surrender of the Belovac at Uxellodunum (51) ended Gallic rule, although full conquest required a winter between December 51 and February 50, after the stubborn pockets of resistance had been crushed.

Roman soldiers profited abundantly from these campaigns, and of course officers even more so. Caesar put his finances in order, enriched the treasury, was generous to his friends, and even set aside a large sum for the future. He flooded Rome with so much gold that the precious metals were devalued by at least thirty percent. The Gallic wars were recorded in one of Caesar’s two surviving works, De bello gallico, written in 52-51, which is not only the most valuable document for understanding the events, but is also considered a masterpiece of classical Latin.

The civil war

Caesar’s other surviving work, De bello civili (literally inferior to the first, perhaps because he did not even have time to revise the manuscript), records the events of the civil war of 49-45. Caesar’s massive rise to power inspired fear among the senators, who were his eternal enemies. On the other hand, many republicans saw in this power the most serious crisis of the republic. In addition, internal circumstances destabilised him: in 52 the Senate appointed Pompey sole consul, and when the Senate side felt strong again, between 51 and 50 Pompey.

In this indecision, Caesar stood before the Rubicon, which separated Gaul from Italy, and, some say by his audacity, others by fate, Caesar was seized by an unstoppable impulse, and, dragging his army behind him, he cried Alea jacta est! This action provoked a civil war: he took Picenum, Umbria and Etruria, travelled to Brindisi to stop Pompey’s crossing, and, though unsuccessful, travelled back up the stream to Rome.

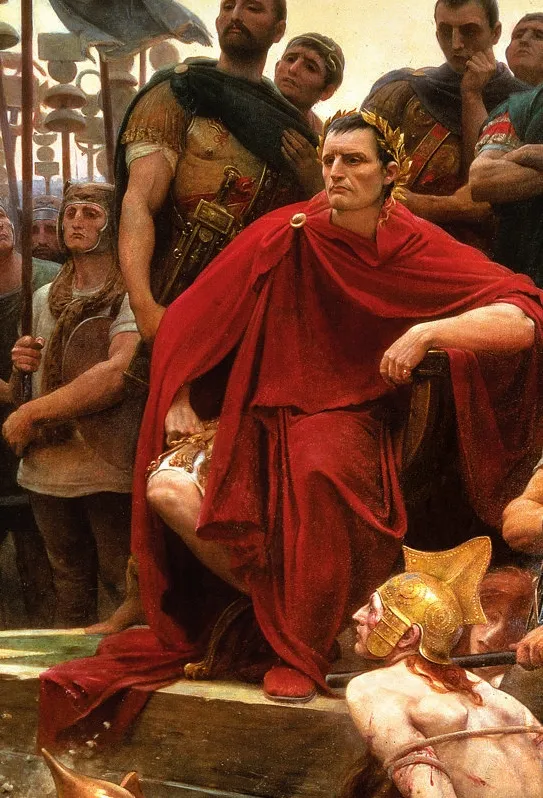

The final battle was to be fought at Pharsalus, which Lucan recorded in an epic. The poet describes Pompey as ‘old’ and ‘a shadow of great honour’, and Caesar as ‘fiery and indomitable’, a man who ‘acted where hope or anger called him’. There, ‘the banner of the lion meets the banner of equality and enmity, the same eagles against each other, the same spears threatening spears’. Caesar was victorious, and Pompey fled to Alexandria, where he died on 28 September 48 BC at the hands of the soldiers of Ptolemy, who was vying with his sister and wife Cleopatra for the throne of Egypt. On hearing of Pompey’s tragic end, Caesar mourned his death.

Caesar in Egypt

Caesar arrived in Egypt with two legions (the 10th and the 12th), totalling some 6,000 men. Once his men were settled in the palace, he attempted to resolve the difficult internal situation in the Nile country, which was divided by the rivalry between the two brothers and their ruling spouses, Ptolemy XIII and Cleopatra VII. Caesar and Cleopatra had an intense and famous love affair, and had a son, King Caesar. Caesar’s succession to the throne of Cleopatra (47 BC), the arrival of Roman troops at the Pharaoh’s palace and the dethronement of Ptolemy XIII led the people, led by councillors loyal to the king, to revolt and attempt to take the palace.

Caesar stood firm in his palace for four months, facing Achilles’ army of 60,000 men from Egypt. Finally, when Mithridates of Pergamum arrived with reinforcements, Caesar undertook one of his most brilliant military campaigns and managed to break through the Egyptian siege to join Mithridates, and the two armies destroyed the Egyptian army in a bloody battle in which Ptolemy XIII was killed. Cleopatra then moved to Rome, where she remained until the dictator’s death.

The war between the Romans was not yet over. Caesar, in his third consulship, was forced to fight again against the senatorial forces at Tapso in April 46, and against the last troops of Pompey’s son at Munda in March 45, when he was already in his fourth consulship. There was little left to do in terms of war. Even during the civil war of 47, he completely defeated Pontius’ archenemy, King Farnaces. Five days after his arrival, he threw himself into the fight and destroyed the enemy in a few hours. He immediately sent a brief but famous account of the events to the Roman Senate: veni, vidi, vici (I came, I saw, I conquered). He was never personally involved in any battle, but his generals won many.

Assassination

Caesar’s actions showed that he was the absolute master of the Roman Republic and the Mediterranean world. The dream of his youth had been realised: absolute power within the legal framework of the Republic. Caesar was both commander-in-chief and dictator. Once again, he showed typical magnanimity towards his enemies; he didn’t forget to pursue agricultural and colonial policies; he increased the number of popular festivals, but was careful to avoid devastating expenses for the state; he enacted economic and financial regulations to protect the underprivileged, tried to moderate the luxurious life of the powerful and limited spending on banquets; he conceived profound political changes, enacted laws that extended Roman citizenship to a greater number of people and began to think of a different world from the one known within the confines of the city of Rome.

Caesar was convinced that in order to maintain his dominion over the East and to be able to successfully complete the final expedition against the Parthians (the only threat to the empire), he needed to be an absolute monarch outside the territorial limits of Rome. This was the trigger. Around sixty members of important families (almost all senators) conspired to overthrow Caesar and restore the legality and legitimacy of the Republic, because they feared that Caesar, with the vast number of positions and privileges he had in his hands, would end up killing the faltering Republic and making himself king.

In fact, some commentators put these boastful and provocative words in his mouth: ‘The Republic is nothing; it is nothing but an empty name, without substance or form’. But for many of them it was certainly an excuse to cover up resentments and sordid desires. Cassius, Brutus and Casca led the conspiracy. Brutus was the son of Caesar’s most famous mistress, Servilia, whom Caesar himself took as his adopted son and bestowed many honours on. Cassius had fought alongside Caesar and was always on the lookout for booty, so it wasn’t difficult to buy him. Finally, Casca was a traditional enemy of Caesar. The other conspirators, who probably had no other goal than to destroy the dictator, acceded to Brutus’ request to honour his deputy, Mark Antony.

On the 15th (15 March), the date of the meeting scheduled to discuss the expedition against the Parthians, Caesar went to the Senate. He went to the Senate despite Calpurnia’s pleas for him not to, as he had ominous dreams during the night. Someone stopped Mark Antony in the Senate antechamber. When Caesar sat down, they surrounded him and attacked him with daggers and knives. According to tradition, in the face of Brutus’ blows, Caesar shouted kai su teknon, a Greek word that was later Latinised into the famous phrase ¡tu quoque, fili mi!.

He was stabbed 23 times and probably only one of them was fatal. While the terrified senators fled (which was not part of the conspirators’ plan), Caesar fell, wrapped in his robes, at the foot of Pompey’s statue. According to Suetonius’ account, the bloody scene (which the prophet had predicted would trigger a new fratricidal war) witnessed the hero’s ultimate grace: “Then, realising that he was the target of innumerable daggers that were piercing his body from all sides, he covered his head with his cloak and, with his left hand, lowered the folds of the cloak by his legs, so as to fall in a more decent manner to fall”. The man who had conquered the world and contributed to irrevocably altering the destiny of a large part of the West and East was now nothing more than a bleeding corpse.

On 17 March, the Senate met urgently to discuss the emergency that followed Caesar’s assassination. A compromise was reached: the assassin was not punished and Caesar himself and his merits were not condemned. The regime fell into the hands of Mark Antony, who was then consul with Caesar. Octavian would implement Caesar’s reforms and become the first emperor of Rome, under the name Caesar Augustus.