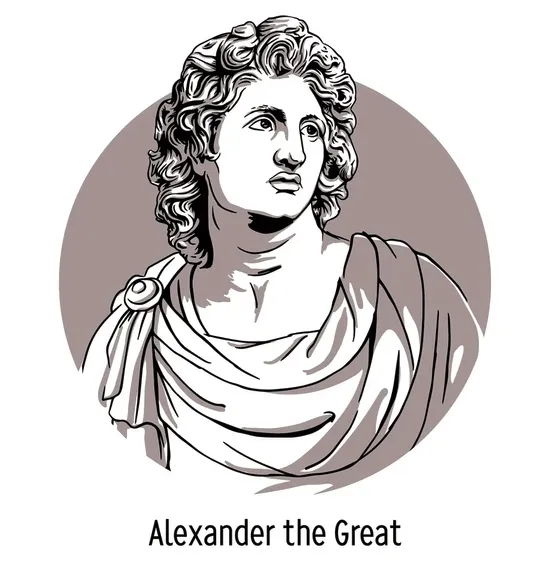

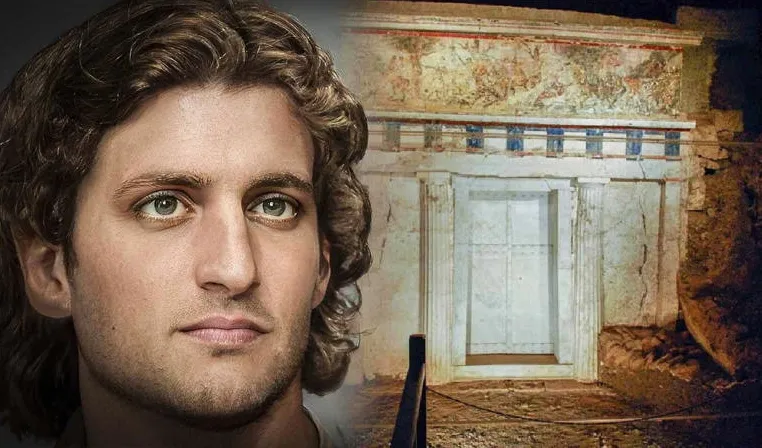

Alexander the Great

For the history of ancient civilizations, the achievements of Alexander the Great were like a whirlwind, and even today we can talk about his life before and after without hesitation. Although his auspicious legacy (the spread of Greek culture to the farthest corners) benefited from a number of favourable circumstances, his biography is a true epic, as historians have pointed out one after the other, a fantastic vision of the Homeric epics in time, and a living example of how some people stand out from their contemporaries and continue to inspire the imagination of future generations.

In the second half of the 4th century BC, a small region in northern Greece, scorned by the arrogant Athenians and labelled barbaric, began a dazzling expansion under the leadership of a military genius, the Macedonian king Philip II. The key to Philip II’s military success was the refinement of the “diagonal battle formation” previously experimented with by Epaminondas. It involved placing cavalry on the attacking flank, but above all it provided mobility for the infantry phalanx and reduced the number of ranks, which previously could only move in one direction. The famous Macedonian phalanx consisted of 16 ranks, each with 16 men, each armed with a helmet, iron shield and a spear called a sarissa.

Alexander was born in October 356 BC in Pella, the capital of ancient Macedon’s Pelagonian region. It was a year of much good fortune for the ambitious Macedonians: one of their most famous generals, Parmenion, defeated the Illyrians; one of their cavalrymen triumphed at the Olympic Games; and Philip had a son, Alexander, who never suffered a defeat in his impressive military career.

Legend has it that on the day Alexander was born, a lavish arsonist set fire to the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus, one of the seven wonders of the world. When he was arrested, he confessed that he had done it to go down in history. The authorities executed him, ordered that even the faintest evidence of his passage through the world should disappear, and forbade anyone to mention his name again. According to legend, the priests of Ephesus saw a clear sign in this disaster that someone had just been born somewhere in the world to rule over the whole of the Orient. According to another version by Plutarch, his birth took place on a night with a hurricane, which the soothsayers interpreted as Jupiter announcing that his existence would be glorious.

Born to conquer

The gods and oracles decreed that he would rule two empires at once, but today it seems that this extraordinary destiny was due more to his own particular reality. In an era when the aristocracy consisted of warriors and conquerors, he was the grandson and son of a king.

When he was born, his father Philip II was a general in the army and the new king of Macedon, having ascended the throne just a few months earlier. He was away from Pella on the Chalkidiki peninsula, celebrating with his soldiers the surrender of the Greek colony of Potidea. When he received the news, he was overjoyed and immediately wrote a letter to Aristotle in Athens to inform him of the event, thanking the gods for having allowed his son to be born in his (the philosopher’s) time and expressing the hope that he would one day become his disciple. She closely supervised the education of her children (Alexander’s sister Cleopatra was about to be born) and instilled her own ambitions in them.

First Lysimachus, then Leonidas, two strict teachers, supervised the prince’s childhood. Nothing superfluous. No frivolity. Nothing that could lead to sexual desire. This strictness obviously suited his character, and he achieved perfect self-control and mastery of his actions.

On Aristotle’s 12th birthday, the king (who had been absent due to his constant campaigns) decided to personally get involved in his education. He was surprised to discover a bright, courageous child, full of judgment, with exceptional talent and a keen interest in everything that was going on around him. Aristotle then entrusted his son to him. From the age of 13 to 17, the prince lived almost exclusively with the philosopher. He studied grammar, geometry, philosophy and, above all, ethics and politics, although in this sense the future king did not follow the ideas of his teacher. Over the years, he acknowledged that Aristotle had taught him “to live with dignity”; he always felt a sincere sense of gratitude towards the Athenian thinker.

Aristotle also taught him to love Homer’s epics, in particular the Iliad, which would eventually become a real obsession for the adult Alexander. At one point, his teacher asked the new Achilles what he intended to do with him once he had gained power. The wise Alexander replied that he would give him an answer when the time came, because you can never be sure about the future. Aristotle was not suspicious of this evasive answer, but was delighted by it and predicted that he would become a great king.

Alexander grew up while the Macedonians increased their dominions and Philip his glory. From an early age, his appearance and his courage were compared to those of a lion, and when he was only fifteen years old, according to Plutarch’s account, an anecdote took place that anticipated his dazzling future. Philip wanted to buy a wild horse of beautiful appearance, but none of his seasoned riders was able to tame it, so he had decided to give up on the idea. Alexander, infatuated with the animal, wanted to have his chance to ride it, although his father did not believe that a boy would succeed where the most experienced had failed. To everyone’s amazement, the future conqueror of Persia climbed onto the back of the horse that would be his inseparable friend for many years, Bucephalus, and galloped on it with unexpected ease.

Healthy, robust and very handsome (according to Plutarch), Alexander, at sixteen and seventeen, embodied the prototype of the ideal young man. In the full vigor of Dorian love, already enriched by Plato’s philosophy, and himself a descendant of Dorians with a teacher who, in turn, had been Plato’s favorite disciple for twenty years, it is not difficult to imagine his sexual awakening. Whether through his mutual admiration with Aristotle himself, or through the latter providing him with other boys as a method of training his spirit, he would have fulfilled, in the era and in the warrior society in which he lived, the role corresponding to his age and condition.

If, as Plato maintained, this kind of love promoted heroism, in Alexander, during those years, the awakening of the hero was imminent. He was soon able to prove both. When his father was wounded at Perinthus, he was called upon to replace him. It was the first time he had taken part in combat, and his conduct was so brilliant that he was sent to Macedonia as regent. In 338 he marched with his father southwards to subdue the Amphissae tribes north of Delphi.

From 380 BC, a visionary Greek, Isocrates, had preached the need to abandon the internecine struggles on the peninsula and form a Panhellenic league. But decades later, the Athenian Demosthenes was concerned about the conquests of Philip, who had taken over the northern Aegean coast. Demosthenes, an outspoken enemy of Philip, took advantage of the king’s absence to persuade the Athenians to arm themselves against the Macedonians. On hearing this, the king set out with his son for Chaeronea and fought the Athenians. The glorious Theban phalanxes, undefeated since their formation by the brilliant Epaminondas, were completely devastated. Every last Theban soldier died in the battle of Chaeronea, where the young Alexander commanded the Macedonian cavalry. Quintus Curtius Rufus relates that after the victory at Chaeronea, where the prince had shown that, despite his youth, he was not only a heroic combatant but also a skilled strategist, his father embraced him and with tears in his eyes said: “My son, find yourself another kingdom worthy of you. Macedonia is too small!”

After the campaigns against the Thracians, Illyrians and Athenians, Alexander, Antipater and Alcibiades were appointed as delegates of Athens to negotiate the peace treaty. It was then that he saw Greece for the first time in all its splendor. The Greece he had learned to love through Homer. The land of which Aristotle had transmitted his pride and passion. During his brief stay he was paid great honors. There he attended gymnasia and palaestrae and trained in the sport of the pentathlon, under the attentive and admiring gaze of adults, who transformed these centers into true “courts of love.” There he was in direct contact with art at the height of Praxiteles’ popularity and with the preliminary moments of the Attic school.

The assassination of Philip

Philip, meanwhile, had brought all of Greece under his authority, with the exception of Sparta. After twenty years of marriage (although for most of that time he had been distant from his wife and their disagreements had been growing), he also had no hesitation in repudiating Olympias and celebrating a new wedding with Atala.

Alexander, who loved his mother, could not bear the offense that the king was inferring to his legitimate wife. Despite this, he was forced to attend the wedding banquet. During the ceremony he criticized his father’s performance, and the father, drunk, went so far as to threaten him with his sword. Outraged and hurt, the prince ran to his mother and begged her to flee with him. With a few loyal followers, mother and son left Pela to take refuge in the palace of their uncle Alexander, king of Molossia in succession to his maternal grandfather.

They lived there until Philip, showing signs of repentance, promised to give the queen the honors that were due to her. However, although Olympias agreed, it is very possible that she was already conspiring with Pausanias to carry out her revenge against Philip and to realize her ambitions of regency. A few weeks later (it was now the spring of 336) they all returned to Epirus, Philip included. The wedding of his daughter Cleopatra to Alexander of Molossia, the bride’s uncle, was being celebrated. During the wedding procession, Philip II was murdered by Pausanias.

It is clear that Olympias was involved in the king’s assassination (or perhaps even responsible for it). But wasn’t Alexander involved? At the age of 20, he took over the kingdom of Macedonia: it was almost a divine plan that finally allowed him to start life in the glory he felt destined for. He set to work immediately. First of all (here Quintus Curtius Rufus says that “he personally punished those who had killed his father”, but this does not seem reliable), he got rid of all those who might oppose him. The year 336 was not yet over when he was appointed “President of the Greek Army” at the People’s Assembly in Corinth.

King of Macedon

In early 335, uprisings in Thrace and Illyria forced him to undertake a brief campaign, during which he conquered and subjugated both regions. He had not yet fully returned to his kingdom. The revolt of the Thebans, combined with that of the Athenians, necessitated a new and urgent campaign to prevent complete unification after rumors spread of his death at Icarus.

But the siege of Thebes was not easy; in comparison, Thrace and Illyria were a breeze. He killed more than 6,000 citizens, enslaved 30,000 soldiers and ordered the complete destruction of the city. However, to show his respect for art and culture, he ordered the house of one of his favorite poets, the Greek poet Pindar, to be spared. Pindar had celebrated the lyrical beauty of the athletes in his “Songs of the Stadium” (Epinikes). Athens surrendered without resistance.

Back in Macedonia, he began preparations for war against the Persian Empire, a war his father had begun (for him it had been the dream of a lifetime) but had been interrupted by his death. He probably traveled to Epirus and Athens several times between the last months of 335 and the spring of 334. His sister Cleopatra, queen of Molossia and ruler of Epirus, sought his advice. In Athens, Alexander’s friend, the sculptor Lysippus of Sikyon, made several busts of Alexander, some of which may have been made at this time.

Conquest of the Persian Empire

Alexander was preparing to leave for Persia when he was told that the statue of the lute-player Orpheus was sweating. Alexander consulted an oracle about the meaning of this omen. The oracle predicted great success for his undertaking, because the gods wanted to show with this sign that it would be difficult for future poets to sing his praises. After entrusting his general Antipater with maintaining peace in Greece, he crossed the Hellespont with 37,000 men in the spring of 334 BC to avenge the crimes of the Persians against their homeland. He never returned. Alexander conquered Thessaly and announced to the local government that the inhabitants of Thessaly would be exempt from taxes forever. He also swore, like Achilles, that he would join his soldiers in as many battles as necessary to strengthen and glorify the country.

When they arrived in Corinth, Alexander was eager to meet the great philosopher Diogenes, who was known for his disdain for wealth and convention and who, despite being over 80 years old, had retained his wisdom. Diogenes was sitting under a shed, warming himself in the sun and looking indifferently at the king. According to Plutarch, when the king said to him, “I am Alexander, king,” Diogenes is said to have replied, “I am Diogenes the Cynic. What can I do for you?” Alexander asked, and the philosopher replied, “Yes, you can do me a favor, and that is by leaving, because your shadow is stealing the sun from me.” Later, the king said to his friend, “If I were not Alexander, I would like to be Diogenes.”

Some time later, another unusual anecdote provided a new legendary conversation, but this time with Dionysius, a famous pirate among the Carians, Tylnians and Greeks, who was captured and brought before the king. The king’s warning did not deter him: “Why do you plunder at sea?” Dionysus replied, “Just as you have the right to plunder on land, I have the right to plunder at sea.” “But I am a king and you are only a pirate,” Dionysus retorted. Dionysius replied, “Our work is the same.” “If the gods have made me a king and you a pirate, I may be a better king than you, but you will never be as skillful and unbiased a pirate as I am.” Alexander is said to have forgiven him.

In June 334, he won a victory over the Persian cavalry at the Granicus. In this bitter and bloody battle, Alexander was close to death, and only his general Kleitos came to his aid at the last minute to save his life. After conquering Halikarnassos, he set out for Phrygia, but stopped in Ephesos on the way, where he met the famous Apelles, who became his personal painter. Apelles lived at the court until Alexander’s death.

In early 333 BC, Alexander and his army reached Gordion. The city was the legendary palace of King Midas and an important trading post between Ionia and Persia. There, the Gordians presented the invaders with an apparently insoluble riddle. A complex knot had tied the chariot of the Phrygian king Gordius. All others had failed, but the fearless Alexander could not resist the temptation to solve the riddle. He cut the rope with the sharp blade of his sword and said mockingly, “It was that easy.” With that, Alexander laid claim to world domination.

He crossed the constellation of Taurus, passed through Cilicia, and in the fall of 333 BC, fought a major battle with King Darius III of Persia on the plains of Issus. Before the battle, Alexander encouraged his troops because he feared the enemy’s numerical superiority. Alexander was confident of victory, because he believed that numbers were no match for wisdom, and that if he acted boldly, the scales would tip in the Greeks’ favor. When the outcome of the war was still uncertain, the cowardly Darius fled, leaving his men in disaster. With the city sacked and the king’s wife and daughter taken hostage, Darius was forced to offer Alexander peace terms that were extraordinarily favorable to the victorious Macedonians. He gave Alexander the western part of the empire and allowed him to marry his most beautiful daughter. The noble Parmenion considered this offer satisfactory and advised his superior: “If I were Alexander, I would accept it,” he replied, ”If I were Parmenio, I would accept it too.”

Alexander was too eager to rule all of Persia to accept this honorable treaty. To do so, he had to control the eastern Mediterranean. After a seven-month siege, he destroyed Tyre, captured Jerusalem, and entered Egypt without meeting any resistance: Before he was known as a Persian conqueror, he was welcomed as a liberator. Alexandria presented itself as the protector of the ancient religion of Amun, and after visiting the temple of Zeus-Amun in the Siwa oasis in the Libyan desert, he proclaimed his divine affiliation in pure Pharaonic style.

Like any good politician, the Temple of Zeus-Amun was a favorite in his political life. Alexander the Great, like any good politician, could not miss this opportunity to increase his prestige and popularity among the Greeks, many of whom were reluctant to accept him. Then (as legend has it), he entered the building alone and listened intently to the reply “as he wished,” as Alexander himself put it. Much ink has been spilled about this visit and the scope of the prophecy. Most historians agree that the oracle told the Macedonians of his divine origin and predicted the establishment of his global empire. In fact, no known text provides information about the oracle’s words.

After returning from the western end of the delta, he founded the city of Alexandria in a favorable natural environment, which became the most famous city of the Greek era. To locate the city, he relied on Homer’s inspiration. He said that poets would appear to him in dreams, reminding him of certain verses in the Iliad. Alexander was unable to use lime to demarcate the city, so he decided to use flour, but birds pecked at the flour, destroying the boundaries. This event was interpreted as a bad omen that Alexander’s influence would spread throughout the land.

By the spring of 331, Alexander had been away from Macedonia for three years, with Antipater as regent; but he does not seem to have considered returning either then or later. He continued his explorations, crossing the Euphrates and the Tigris, meeting the last army of Darius III on the plains of Jogamela, and putting an end to the Achaemenid dynasty at the Battle of Abela. The impressive Persian army in this battle possessed tremendous shock power: Elephants.

Parmenion favored attacking under cover of darkness, but Alexander did not want to hide his victory from the sun. That night, he slept peacefully and confidently while his men admired his strange calm. He came up with an ingenious plan to avoid the enemy’s maneuvers. His best weapon was cavalry speed, but he also relied on his opponent’s lack of fortitude and planned to decapitate the army at the first opportunity. Indeed, Darius once again showed his weakness and fled as Alexander approached, suffering another ignominious defeat. All the capitals were opened to the Greeks. Upon entering Persepolis, Alexander ordered the occupation of Susa, Babylon, and Ecbatana almost simultaneously. 330 In July, Darius was assassinated. Pisos, the governor of Bactria, ordered the execution of Darius after his overthrow.

Alexander then conquered the eastern provinces and continued his march eastward. Since then, many tales and legends have accumulated around the seemingly invincible demigod. History tells us that he wore a Persian shawl, which was familiar to the Greeks, symbolizing that he was the king of two kingdoms. We know that he ordered the burning of Persepolis in retaliation; that in a fit of rage he killed Cletus who saved his life at Granicus with a spear; that he ordered the murder of Callisthenes, the nephew of the philosopher Aristotle, for writing poems that hinted at his cruelty; and that he married the Persian princess Roxana. He also married the Persian princess Roxana, contrary to Greek expectations. Alexander even went on an expedition to India, where he had to fight the noble Hindu king Porus. As a result of this tragic battle, his faithful horse, Bucephalus, died, and in his honor, he founded a city called Bucephalia.

Back to

But his army suffered heavy losses during the founding of New Alexandria. Exhausted and weakened, he reached Hephaestus (the easternmost point he reached in the east) in 326 and had to continue his return after the soldiers revolted. On the way back, the army split into two: General Nearchus sought the sea route, while Alexander led the bulk of the army across the hellish Jethros Desert. Thousands perished in the effort. Thirst was more devastating than enemy spears. Despite the heavy losses, the army managed to reach its destination, and a wedding of eighty generals and ten thousand soldiers was held to announce the conquest of the East.

Upon arriving in Babylon, he did not hesitate to order the execution of the Macedonians who opposed him. His plan was to create a new army of Greeks and barbarians to suppress the liberal traditions of the Macedonians. He wanted to create a mixed nation and adopt the rituals of the Achaemenid dynasty, while seeking and gaining the support of eastern families. In this way, he believed he could ensure the success of his plans for world domination. Although he continued to conduct campaigns and plan new ones until he could no longer speak on his deathbed, one event shattered his confidence: Hephaestion’s death, and Alexander was in a state of anxiety and turmoil.

Alexander married Roxana during the Battle of Bactria, and after the marriage he had his only son, Alexander IV. In his desire for racial integration, he also arranged marriages between Macedonian soldiers and eastern women, and married Statera in Susa. She trusted Ptolemy, who was her cousin (perhaps her half-brother) and her commander-in-chief. She also had Nearchus, who was also her officer and had been her companion and friend since childhood. But Hephaestus was more than all of these: He was her friend, perhaps even her lover, but above all he was a wise man and a like-minded man, and they admired each other.

Hephaestion died in October 324, while they were in Ecbatana, and his death saddened the emperor so much that he became depressed when he died a few months later. 325 On his return from India, he was severely wounded in the chest while marching along the Indus River, and the return journey across the Gedrosian Desert in harsh conditions aggravated his health; in the late summer of 324 he decided to rest for a while, and stayed in the summer palace in Ecbatana with Roxana and his friend Hephaestion. His wife became pregnant. His friend suddenly fell ill and died. Alexander carried the body to Babylon and arranged Hephaestion’s funeral.

He immediately began a new journey to explore the Arabian coast. While sailing down the Euphrates River, he contracted the deadly disease malaria.3 In June 323, Alexander died in the majestic and now ruined pyramid of Bel Marduk, and on his deathbed he gave the ring, the symbol of the king, to Perdiccas, who had been Hephaestion’s assistant since his death. Alexander was thirty-three years old. He was accompanied by Roxana. Statera remained in Susa, living in the harem of her grandmother’s palace, Sisyphus. Behind the walls that protected the interior of the city, the Euphrates continued to flow. On the same day, having nothing left but his miserable barrels, and having left mankind nothing, at the age of about ninety, he died in Corinth of his counterpart, Diogenes the frowning philosopher, Diogenes the frowning philosopher .

The strange phenomenon of Alexander’s indestructible remains, exacerbated by the prevailing Babylonian heat, would lead to his canonization in the Christian era, as it was believed to be a miracle. There was no such tradition that attracted the attention of biographers in the fourth century BC. A more accurate explanation is that he died a clinical death much later than was believed at the time.

Cassander was the eldest son of Antipater, who was Alexander’s guardian when he traveled to Asia and who became king of Macedonia after the assassination. After the death of Alexander the Great, his sister Cleopatra continued to rule Mauritius for many years. His mother Olympias disputed the Macedonian regency with Antipater and allied herself with the new regent Polyperchus in 319 B.C. When she realized her life’s ambition, she was killed in Pydna in 316 B.C. Ptolemy, one of her top commanders, wrote Alexander’s biography ; Ptolemy became king of Egypt and inaugurated a dynasty, the Ptolemaic dynasty, which lasted until 30 BC, the year of the death of Egypt’s last queen, the famous Cleopatra.