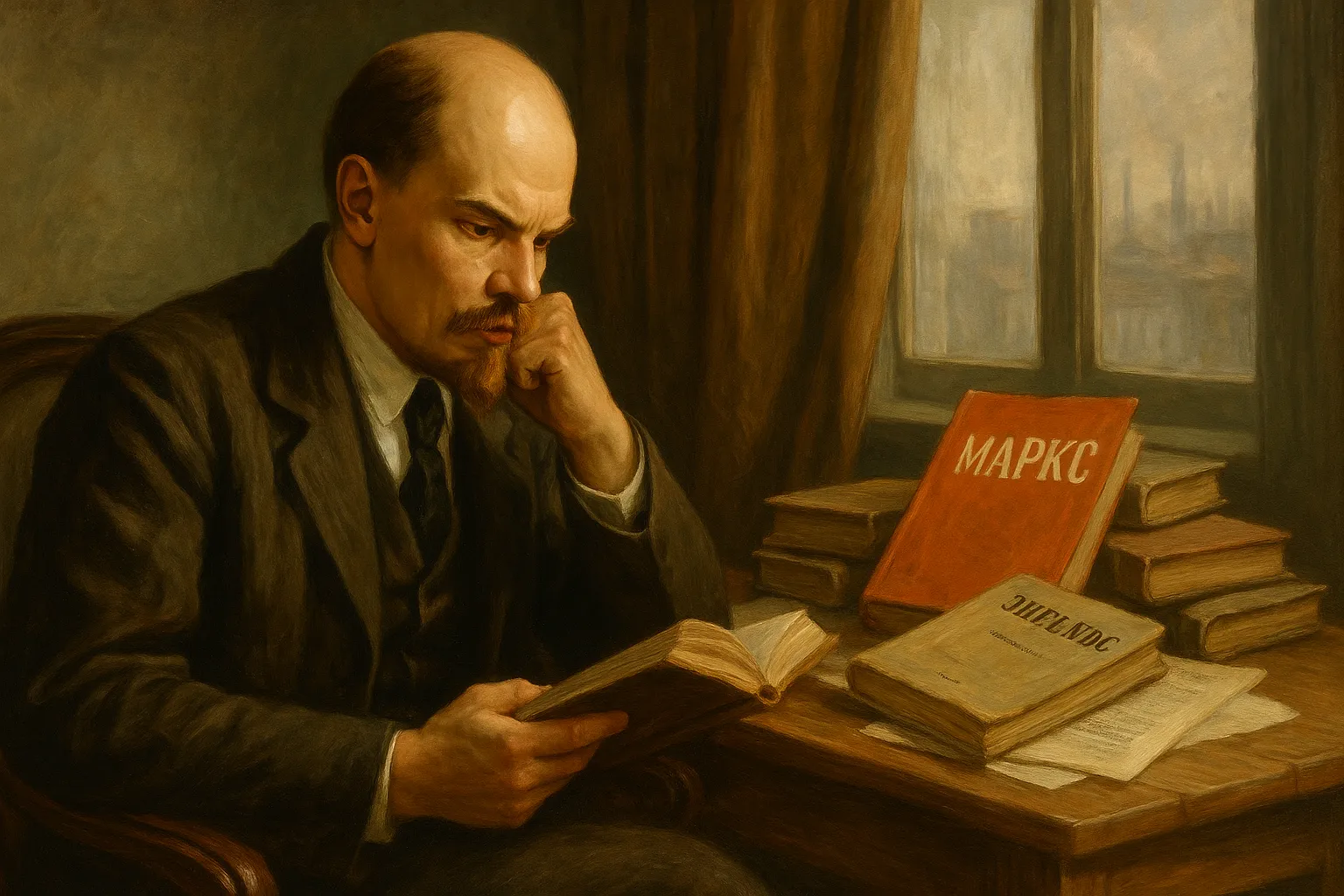

Biography of Vladimir Lenin: The architect of the revolution that shook the world

The story of the 20th century cannot be told without the towering figure of Vladimir Lenin. Leader of the Russian Revolution, founder of the world’s first socialist state, and a man whose influence reverberated across continents, Lenin remains one of history’s most polarizing figures. For some, he was a visionary liberator; for others, a ruthless revolutionary who paved the way for totalitarian regimes. Behind the myths lies a deeply human story—a tale of ideas, ambition, sacrifice, and power.

This is the life of the man who changed the course of world history.

A Youth Shaped by Repression (1870–1887)

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, known to history as Lenin, was born on April 22, 1870, in Simbirsk, Russia (now Ulyanovsk). He came from a well-educated, middle-class family. His father, Ilya Ulyanov, was a respected school inspector, and his mother, Maria Alexandrovna, came from a cultured background.

As a child, Lenin displayed remarkable intelligence and discipline. But a family tragedy would forever alter his life: in 1887, his older brother Aleksandr Ulyanov was executed for plotting to assassinate Tsar Alexander III. This event ignited in young Vladimir a deep hatred for the monarchy and a lifelong commitment to revolutionary change.

Political Awakening and Intellectual Formation (1887–1895)

At age 17, Lenin enrolled at Kazan University to study law but was quickly expelled for participating in student protests. He continued his studies privately, eventually earning his law degree in 1891.

During this period, Lenin immersed himself in revolutionary literature, particularly the works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Marxism provided him with a powerful framework to analyze Russia’s deep social inequalities—a feudal empire struggling to modernize amid industrial expansion.

In 1893, he moved to St. Petersburg, where he joined clandestine Marxist circles, organizing workers and distributing revolutionary propaganda.

Arrest, Siberian Exile, and Marriage (1895–1900)

In 1895, Lenin co-founded the League of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class, one of Russia’s first Marxist organizations. His activities quickly drew the attention of the tsarist police.

Arrested and sentenced to three years of exile in Siberia, Lenin used this time to study, write, and refine his revolutionary ideas. During his exile, he married Nadezhda Krupskaya, a fellow Marxist who would remain his partner in both life and politics.

After completing his sentence, Lenin left Russia, determined to build a revolutionary movement from abroad.

The Rise of Bolshevism (1900–1905)

While in exile across Europe, Lenin became an influential figure within the international socialist movement. In 1900, he launched the underground newspaper Iskra (“The Spark”), which spread Marxist ideas among Russian workers and intellectuals.

In 1903, at the Second Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), Lenin led a critical split within the movement:

-

The Bolsheviks (“majority”) under Lenin advocated for a highly disciplined, centralized party of professional revolutionaries.

-

The Mensheviks (“minority”) favored a more democratic and open membership structure.

This division would define the future of Russian socialism for decades.

The 1905 Revolution and Renewed Exile

The 1905 Revolution, sparked by the Bloody Sunday Massacre in St. Petersburg, marked Lenin’s first major revolutionary opportunity. However, the rebellion ultimately failed due to internal disorganization and brutal repression.

Forced once again into exile, Lenin traveled throughout Europe—Switzerland, Germany, France—continuing to write, debate, and organize. He clashed with rival Marxists, refining his belief that only a tightly controlled revolutionary vanguard could successfully overthrow the autocracy.

For Lenin, revolution was not inevitable; it had to be actively orchestrated through careful organization and unwavering resolve.

The February Revolution: An Opening for Power (1917)

The outbreak of World War I plunged Russia into economic collapse and social chaos. Lenin, fiercely opposed to the “imperialist war,” called on workers to turn the conflict into a global class struggle.

In February 1917, mass protests in Petrograd forced Tsar Nicholas II to abdicate. A weak Provisional Government took power but struggled to govern amid growing unrest.

With Germany’s assistance, Lenin returned to Petrograd, seeing the moment as ripe for revolution. In his famous April Theses, he demanded:

-

Immediate withdrawal from World War I.

-

Power transferred to the soviets (workers’ councils).

-

Nationalization of land and banks.

His radical message electrified workers and soldiers disillusioned with the moderate Provisional Government.

The October Revolution: Seizing Power (1917)

Throughout 1917, Lenin worked tirelessly to erode the Provisional Government’s authority. On October 25 (November 7, New Style), 1917, the Bolsheviks stormed the Winter Palace in Petrograd, toppling the government in what became known as the October Revolution.

With remarkably little bloodshed, Lenin and the Bolsheviks seized control, proclaiming the world’s first socialist state.

But the revolution was only beginning.

Civil War and the Red Terror (1918–1921)

Almost immediately, Lenin faced fierce opposition:

-

The White Army (royalists, liberals, nationalists).

-

Foreign intervention (Britain, France, the U.S., Japan).

-

Peasant uprisings and anarchist resistance.

During the brutal Russian Civil War, Lenin authorized the Red Terror, led by the secret police Cheka, which conducted mass arrests, executions, and suppression of perceived enemies.

Economically, Lenin implemented War Communism—nationalizing industries, requisitioning crops, and centralizing control—policies that brought widespread famine and hardship but ensured military victory.

By 1921, after years of devastating conflict, the Bolsheviks had secured total control.

Founding the USSR and Introducing the NEP (1922)

To formalize the new political order, Lenin proposed the creation of a new multinational state. In 1922, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was officially established.

Facing economic collapse, Lenin introduced the New Economic Policy (NEP), which temporarily reintroduced limited private trade and small-scale capitalism to stabilize the economy—a pragmatic retreat he saw as necessary for the revolution’s survival.

The NEP succeeded in reviving production but sparked debate within the Communist Party about the future direction of socialism.

Decline, Political Infighting, and Death (1922–1924)

In 1922, Lenin suffered the first of several debilitating strokes that gradually paralyzed and silenced him.

As his health deteriorated, he grew increasingly concerned about the rising power of Joseph Stalin, whom he criticized sharply in his Testament, warning that Stalin was “too rude” to wield unchecked authority.

Despite his warnings, Lenin’s declining influence allowed Stalin to consolidate power quietly. On January 21, 1924, Lenin died at the age of 53.

His embalmed body was placed in a mausoleum in Moscow’s Red Square, where it became a shrine of Soviet state ideology.

Inspiration or Warning?

Lenin’s legacy remains deeply divisive:

-

Admired by supporters: For liberating Russia from monarchy, founding the world’s first socialist state, inspiring anti-colonial movements, and championing workers’ rights.

-

Criticized by opponents: For dismantling democracy, unleashing repression, establishing a one-party dictatorship, and laying the groundwork for Stalin’s totalitarian rule.

Objectively, Lenin:

-

Adapted Marxist theory to Russia’s unique conditions.

-

Emphasized the necessity of a centralized revolutionary vanguard.

-

Sparked a global ideological struggle that defined much of the 20th century.

Even after the collapse of the USSR in 1991, Lenin remains a symbol—both of hope for revolutionary idealists and a cautionary tale for critics of authoritarian power.

Vladimir Lenin was not simply a Marxist theorist; he was a brilliant political tactician who combined radical ideology with pragmatic ruthlessness to seize and retain power.

His revolution reshaped Russia and set off global waves of change that would shape international politics for nearly a century. The duality of his legacy—visionary liberator for some, authoritarian despot for others—reflects the complexities inherent in revolutionary upheaval.

More than a century after the October Revolution, Lenin remains one of the most consequential, controversial, and studied figures in modern history—a man whose ideas still fuel debate, inspire movements, and caution against the dangers of absolute power.