Biography of Martin Luther: The man who defied Rome and sparked the Protestant Reformation

Martin Luther was not just a theologian or a rebellious monk—he was the driving force behind one of the most transformative movements in Western history. Born in an age of spiritual corruption and ecclesiastical power, Luther broke the Catholic Church’s monopoly on salvation and radically changed how millions understood faith, authority, and grace. His legacy has inspired reverence, criticism, and scholarly analysis for centuries. This is the biography of a man who, armed with Scripture and unshakable conviction, forever altered the religious and cultural landscape of Europe.

Early Life (1483–1505)

Martin Luther was born on November 10, 1483, in Eisleben, in the Holy Roman Empire. His father, Hans Luder, was a former peasant who rose into the middle class through copper mining. Ambitious and pragmatic, Hans wanted his son to become a successful lawyer.

Luther was a bright child, educated in Magdeburg and Eisenach, before enrolling at the University of Erfurt in 1501. He earned his Master of Arts in 1505 and began studying law, following his father’s wishes.

However, a life-changing event altered his path: caught in a violent thunderstorm, Luther vowed to become a monk if he survived. True to his word, on July 17, 1505, he entered the Augustinian monastery in Erfurt—much to his father’s dismay.

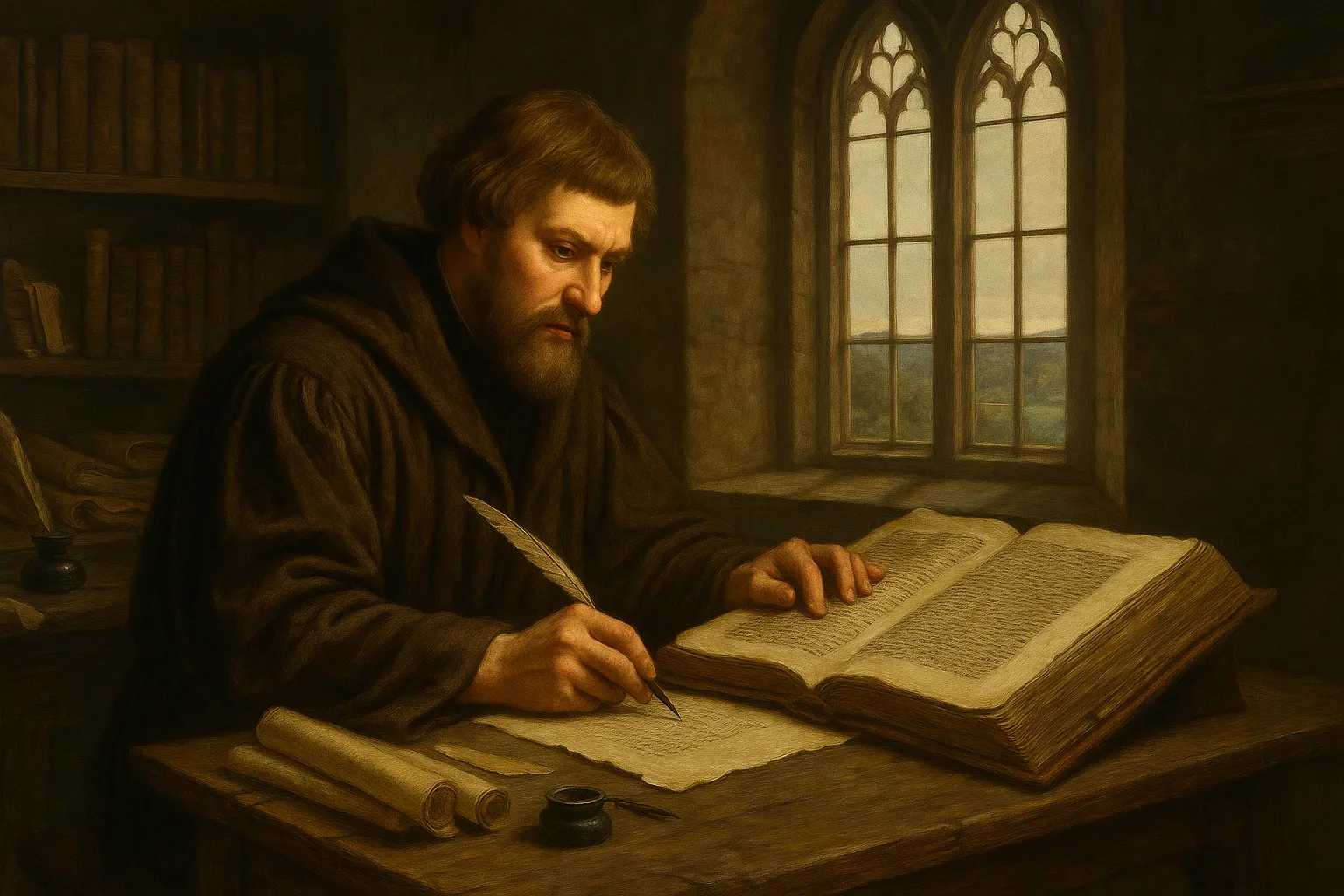

Monkhood and Theological Awakening (1505–1517)

Despite his strict monastic lifestyle—marked by fasting, prayer, and confession—Luther could not find peace. He was tormented by guilt and the fear of divine judgment. Seeking answers, he delved deeply into Scripture and theology.

He was sent to Wittenberg, where he earned a doctorate in theology in 1512 and became a professor of biblical studies at the university. His lectures gained popularity, and his intellectual rigor stood out.

It was during this time that Luther began to question key doctrines of the Catholic Church, particularly those related to salvation, penance, and indulgences. He concluded that salvation came by faith alone, not by works or rituals.

The Indulgence Controversy and the 95 Theses (1517)

The Church’s sale of indulgences—certificates believed to reduce punishment for sins—deeply angered Luther, especially when Johann Tetzel, a Dominican friar, began selling them near Wittenberg.

On October 31, 1517, Luther posted his 95 Theses on the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg. These theses challenged the theological legitimacy of indulgences and questioned papal authority.

Thanks to the printing press, the 95 Theses spread rapidly throughout Europe. What began as an academic debate quickly evolved into a religious and political movement, placing Luther at the center of an unfolding revolution.

Breaking with Rome (1518–1521)

Luther was summoned to appear before Cardinal Cajetan in 1518 and later debated Johann Eck in Leipzig in 1519. There, he declared that only Scripture held ultimate authority, not the pope or church councils.

In 1520, Luther published three landmark texts:

-

“To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation” – urging secular rulers to reform the Church.

-

“The Babylonian Captivity of the Church” – attacking the sacramental system.

-

“The Freedom of a Christian” – explaining salvation by faith and spiritual liberty.

That same year, Pope Leo X issued the bull Exsurge Domine, threatening excommunication. Luther responded by publicly burning the document.

At the Diet of Worms in 1521, Emperor Charles V demanded Luther recant his writings. Luther refused, famously stating, “Here I stand, I can do no other. God help me.” He was declared a heretic, but protected by Frederick the Wise, who hid him at Wartburg Castle.

Translating the Bible and the Birth of Lutheranism (1521–1525)

While in hiding, Luther began his monumental task: translating the New Testament into German. This project not only democratized access to Scripture but also influenced the development of the German language.

Meanwhile, Luther’s ideas gave rise to Lutheran churches across Germany and beyond. His call for reform resonated far and wide, inspiring both moderate and radical reformers.

However, trouble brewed. In 1524, the German Peasants’ War erupted. Some peasants cited Luther’s writings as justification for rebellion. Horrified by the violence, Luther condemned the uprising in “Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants,” alienating many former allies.

A Social and Religious Reformer

Martin Luther reshaped not only theology but society itself. He simplified the mass, allowed communion in both kinds, rejected clerical celibacy, and encouraged congregational singing. His emphasis on personal Bible reading fostered mass literacy across Protestant regions.

In 1525, he married Katharina von Bora, a former nun. They had six children, and their home became a model for Protestant family life, showing that pastors could also be husbands and fathers.

His teachings helped legitimize political autonomy from the Church, strengthened national identities, and laid the groundwork for modern concepts of religious freedom and individual conscience.

Later Years and Death (1525–1546)

Luther’s later writings were increasingly polemical. He wrote harshly against the papacy, radical sects, and most controversially, the Jewish population, particularly in “On the Jews and Their Lies” (1543)—a deeply antisemitic text that remains a controversial stain on his legacy.

He remained active in organizing church structures and mentoring reformers, but his health declined in the 1540s. On February 18, 1546, he died in Eisleben, aged 62.

Luther was buried at the Castle Church in Wittenberg, beneath the very place where he had nailed his 95 Theses.

Legacy of Martin Luther

Luther’s legacy is vast and complex. He is rightly called the Father of the Protestant Reformation, and his ideas gave birth to a wide array of Protestant denominations, including Lutheranism, Calvinism, and Anglicanism.

His insistence on sola scriptura (Scripture alone), sola fide (faith alone), and sola gratia (grace alone) reshaped Christian theology and practice.

Moreover, his work promoted:

-

Universal education: schools for boys and girls.

-

Vernacular Bibles: the Bible in every home.

-

The priesthood of all believers: empowering laypeople.

-

Religious pluralism: ultimately paving the way for tolerance.

Yet, his legacy also includes darker aspects—his intolerance toward dissenters and his anti-Jewish writings, which demand historical accountability.

Despite the controversies, Luther’s influence remains monumental. In 2017, the 500th anniversary of the Reformation was commemorated globally, including joint Catholic-Protestant celebrations, reflecting progress in interfaith dialogue.

Martin Luther was more than a rebel monk. He was a revolutionary mind, a bold reformer, and a powerful voice in the face of institutional power. His unwavering commitment to Scripture and truth shook the foundations of medieval Christianity and gave birth to a new religious era.

His ideas have shaped modern democracy, education, and freedom of belief. Whether viewed as a prophet, a heretic, or a visionary, Martin Luther’s name remains etched in history—not merely as a symbol of protest, but as a testament to the transformative power of conviction.