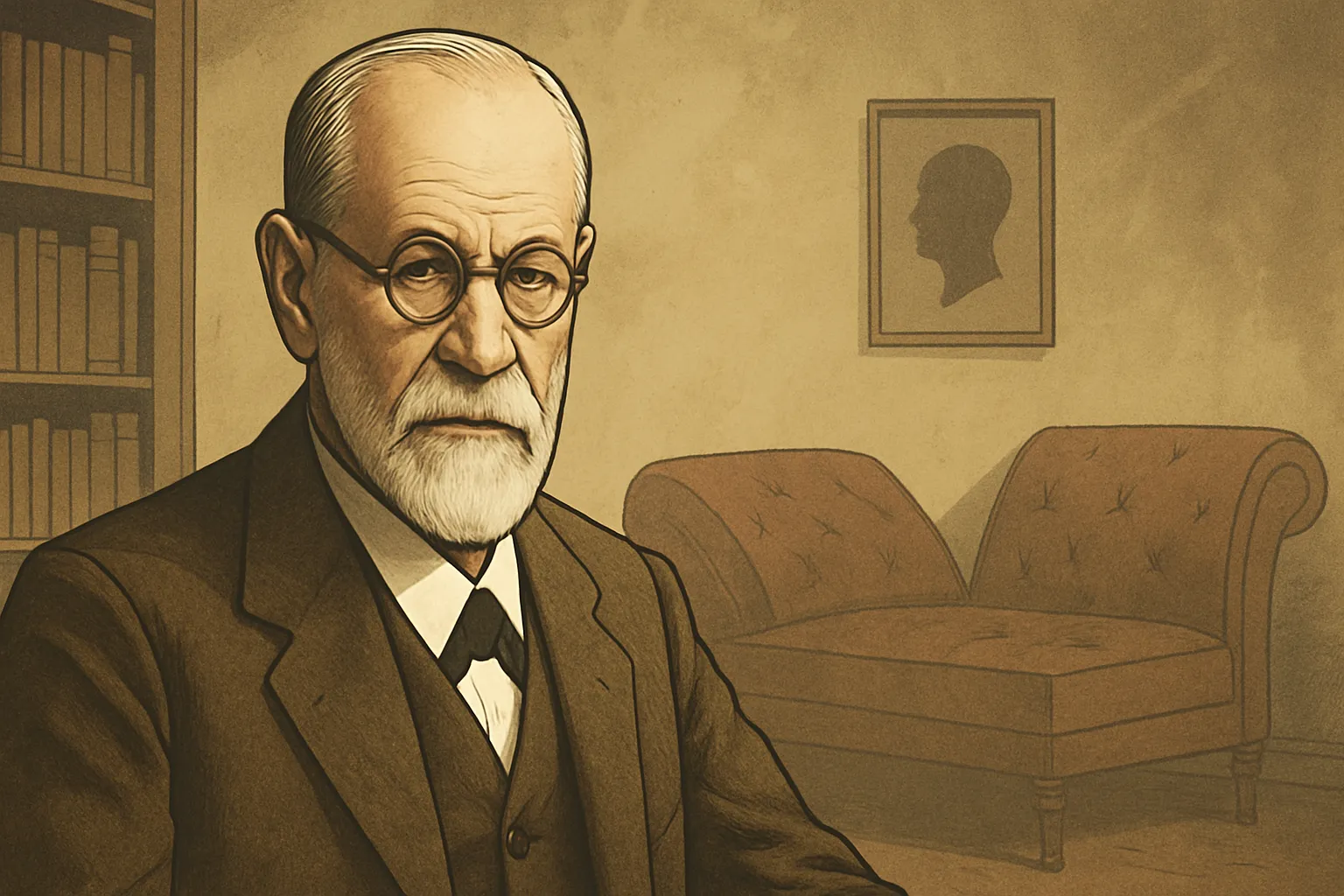

Biography of Sigmund Freud: the father of psychoanalysis

Few figures have left such a profound mark on the fields of psychology, philosophy, and modern culture as Sigmund Freud. Born during a time of radical change, Freud challenged the established norms of scientific and social thought to explore the complexities of the human mind. His work gave rise to psychoanalysis, a discipline that transformed not only psychotherapy but also how we understand human behavior, dreams, sexuality, and the unconscious.

Throughout his life, Freud faced numerous controversies and challenges, both personal and professional. Nevertheless, his legacy endures today as one of the most influential thinkers of the 20th century.

Childhood and Education

Sigmund Freud was born on May 6, 1856, in Freiberg, Moravia (now Příbor, Czech Republic), into a middle-class Jewish family. His father, Jakob Freud, was a wool merchant, and his mother, Amalia, was only 20 years old when she gave birth to Sigmund, the eldest of eight children. The family moved to Vienna when Freud was just four years old—a city that would become the epicenter of his life and intellectual work.

From a young age, Freud demonstrated exceptional academic talent. He was admitted to the University of Vienna at age 17, initially studying law but quickly shifting his focus to medicine and biology. Under the influence of prominent scientists like Ernst Brücke, Freud became deeply interested in the functioning of the nervous system, neuroanatomy, and physiology.

During his university years, Freud conducted pioneering research on nerve tissue, publishing several scientific papers before earning his medical degree in 1881. However, his true passion lay in exploring the darker mysteries of the human mind.

Medical and Neurological Influences

After obtaining his medical degree, Freud worked at the General Hospital of Vienna, specializing in neurology. His early clinical work included patients suffering from neurological disorders inexplicable by the medicine of the time, such as hysteria and paralysis without physiological cause.

In 1885, Freud received a grant to study in Paris under Jean-Martin Charcot, a renowned neurologist who used hypnosis to treat hysteria. This encounter marked a turning point in Freud’s career. Charcot taught him that physical symptoms could have underlying psychological causes—a revolutionary idea that would form the foundation of psychoanalysis.

Upon returning to Vienna in 1886, Freud opened his private practice and married Martha Bernays, with whom he had six children. During these early years of clinical practice, Freud began developing his own theories on the unconscious, childhood sexuality, and defense mechanisms.

The Beginnings of Psychoanalytic Theory

One of the foundational moments of psychoanalysis was Freud’s collaboration with his colleague Josef Breuer. Together they treated the case of “Anna O.” (Bertha Pappenheim), a young woman suffering from severe hysterical symptoms. Using the “cathartic method,” in which the patient recounted repressed traumatic experiences, her symptoms began to subside.

This case led Freud and Breuer to publish Studies on Hysteria in 1895, introducing the concept that neurotic symptoms had roots in unconscious emotional conflicts.

Though their professional paths soon diverged, this work laid the groundwork for the psychoanalytic method: the unconscious as the true driver of human behavior.

The Development of Psychoanalysis

As Freud delved deeper into the study of the unconscious, he developed revolutionary concepts:

-

Repression: painful memories are expelled from conscious awareness.

-

Oedipus complex: unconscious sexual desires directed toward the opposite-sex parent.

-

Dreams as wish fulfillment: presented in his famous work The Interpretation of Dreams (1900).

-

Transference: patients project unconscious feelings onto the therapist.

In The Interpretation of Dreams, Freud first proposed a structural model of the mind, dividing it into the unconscious, preconscious, and conscious. He later expanded this model into the famous triad: id, ego, and superego.

Early Controversies and Opposition

Freud’s ideas were initially met with skepticism by the Viennese medical community. His theories on childhood sexuality, the unconscious, and repressed impulses were scandalous for the moral standards of the late 19th century.

However, Freud gathered a circle of followers who formed the core of the early psychoanalytic movement. Among them were Carl Jung, Alfred Adler, Wilhelm Stekel, and Otto Rank.

Theoretical differences soon emerged:

-

Jung broke away to develop analytical psychology.

-

Adler founded individual psychology.

-

Freud remained the central figure of classical psychoanalysis.

These splits reflected both the richness of Freud’s original ideas and their inherently controversial nature.

The International Expansion of Psychoanalysis

Despite early opposition, psychoanalysis began spreading internationally. In 1909, Freud was invited to lecture at Clark University (Massachusetts, USA), marking his triumphant entry into American academia.

Throughout the 1910s and 1920s, psychoanalytic societies were founded in various countries. Freud continued publishing seminal works, including:

-

Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920)

-

The Ego and the Id (1923)

-

The Future of an Illusion (1927)

-

Civilization and Its Discontents (1930)

In these works, he explored topics such as the death drive, religion, civilization, and humanity’s destructive nature.

Nazi Persecution and Exile

With the rise of Nazism in Germany and Austria, Freud—a Jewish intellectual—became a target. In 1938, after the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany (Anschluss), pressure on Freud and his family became unbearable.

Thanks to the intervention of friends and supporters, including Marie Bonaparte, Freud emigrated to London with his family. There, he would spend his final years as many of his books were publicly burned by the Nazis.

His famous remark upon hearing about the book burnings was:

“What progress we are making. In the Middle Ages they would have burned me; now they are content with burning my books.”

Final Years and Death

In London, Freud lived under medical care due to the jaw cancer he had battled since 1923. Painful surgeries failed to stop the disease’s progression.

On September 23, 1939, Freud passed away in his London home at the age of 83. His death marked the end of an era but the beginning of a legacy that continues to influence multiple disciplines.

Freud’s Legacy

Few intellectuals have been as influential and controversial as Freud. His ideas have profoundly impacted:

-

Clinical psychology: modern talk therapy traces its roots to psychoanalysis.

-

Popular culture: terms like “unconscious,” “Oedipus complex,” and “Freudian slip” are everyday language.

-

Literature and art: numerous writers and artists drew inspiration from his theories.

-

Philosophy: thinkers like Foucault, Lacan, and Marcuse reinterpreted his work.

-

Neuroscience: while debated, some ideas about unconscious processes remain research topics.

Even his harshest critics acknowledge that Freud revolutionized how we conceptualize the human mind.

Criticism of Psychoanalysis

Though undoubtedly influential, Freud’s theories have faced heavy criticism:

-

Accusations of lacking scientific rigor.

-

Clinical methods difficult to replicate or falsify.

-

Overemphasis on sexuality.

-

Cult-like behavior within the psychoanalytic movement.

Modern psychology, particularly cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), has largely supplanted psychoanalysis in clinical practice. Nevertheless, the historical and cultural value of psychoanalysis remains indisputable.

Freud in the 21st Century

Today, Freud is studied both in psychology departments and in philosophy, literature, cultural studies, and intellectual history programs.

Although many of his core theories have been revised, reformulated, or even discarded, he remains a key reference point in understanding the development of thought about the mind and human behavior.

Sigmund Freud was much more than the founder of psychoanalysis; he was a true explorer of the darkest corners of the human psyche. With a blend of brilliant intuition, scientific perseverance, and keen observation, he opened pathways that we still follow today.

His legacy is complex, fascinating, and controversial—just like the human beings whose minds Freud dared to unravel.