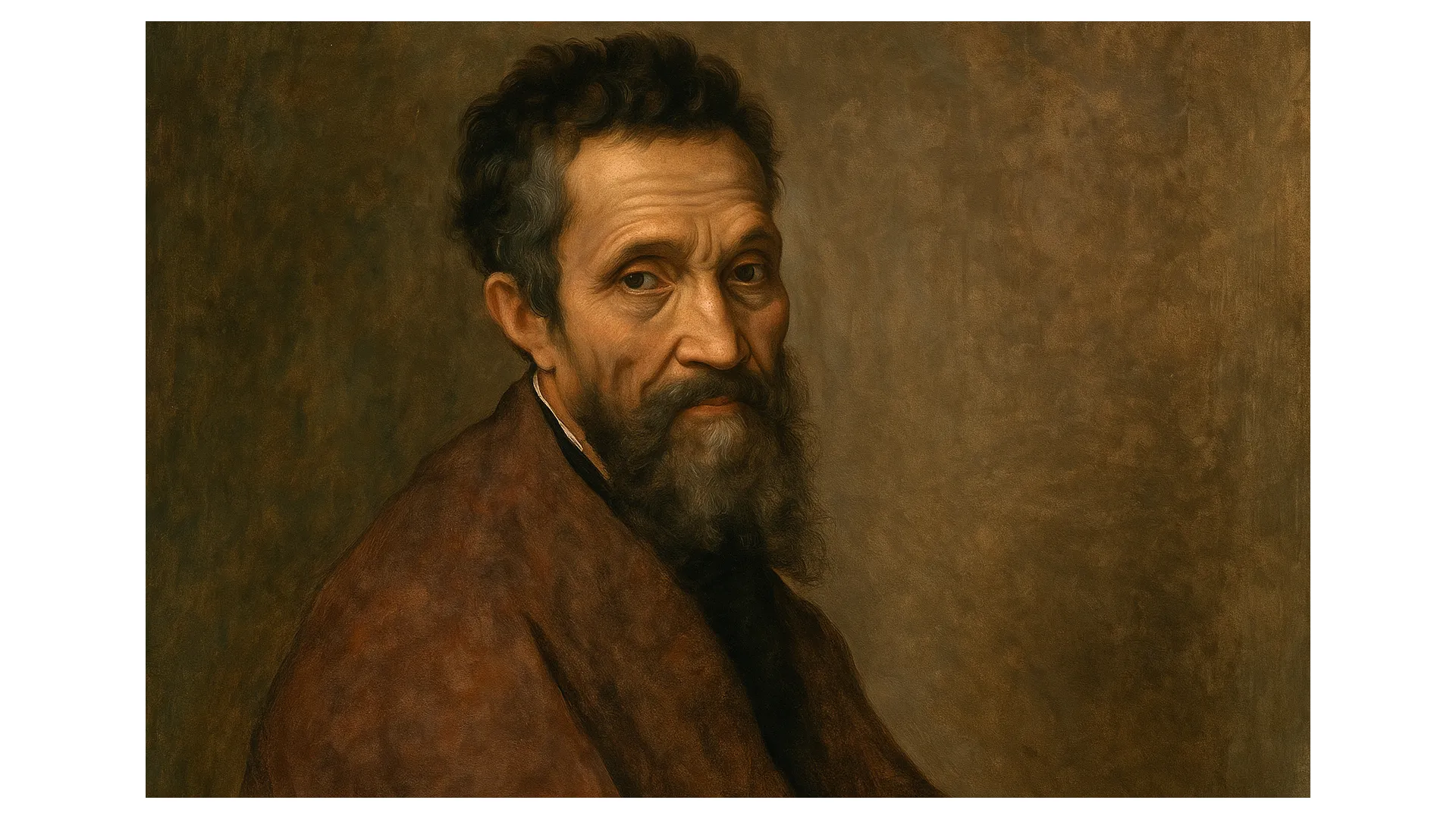

Biography of Michelangelo Buonarroti: The divine genius of the Renaissance

Few names in the history of art carry as much weight and reverence as Michelangelo Buonarroti. A polymath of unmatched skill and vision, Michelangelo was not only a sculptor but also a painter, architect, and poet. His works are some of the most iconic achievements of the Renaissance, and his influence has reverberated across centuries. This article explores the life, passions, and lasting legacy of this extraordinary figure, offering an in-depth look at the man behind masterpieces like the Sistine Chapel ceiling, David, and the Pietà.

The Birth of a Renaissance Titan

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni was born on March 6, 1475, in Caprese, a small town in the Republic of Florence. His father, Ludovico di Leonardo Buonarroti Simoni, was a minor noble and held several governmental posts. Despite their noble status, the Buonarroti family was not wealthy, and young Michelangelo’s early life was modest.

At an early age, Michelangelo was sent to live with a stonecutter and his family in Settignano, a village known for its marble quarries. It was here that his fascination with sculpture began to take shape. According to legend, he absorbed the art of carving “with his mother’s milk.”

By the age of 13, Michelangelo had secured an apprenticeship with Domenico Ghirlandaio, one of Florence’s leading fresco painters. His prodigious talent quickly became evident, prompting Lorenzo de’ Medici—the de facto ruler of Florence and a major patron of the arts—to invite Michelangelo into his household. This period marked the beginning of Michelangelo’s immersion in classical learning and artistic refinement.

Mastery in Marble

Michelangelo’s early works in sculpture set the tone for a career defined by technical precision and emotional depth. Among his first major commissions was the “Bacchus” (1496–1497), a life-sized statue depicting the Roman god of wine. Though the piece received mixed reviews, it showcased Michelangelo’s ability to imbue marble with a sense of fluidity and motion.

Shortly afterward, Michelangelo carved the “Pietà” (1498–1499), a sculpture of the Virgin Mary cradling the dead body of Christ. Completed when he was only 24 years old, the work was an instant masterpiece. Its beauty, serenity, and anatomical perfection cemented Michelangelo’s reputation as one of the greatest sculptors of his generation.

A Symbol of Florentine Pride

Perhaps no single work defines Michelangelo more than his statue of “David.” Carved from a single block of Carrara marble between 1501 and 1504, the statue stands over 17 feet tall and represents the biblical hero at the moment before his battle with Goliath. Unlike earlier depictions, Michelangelo’s David is nude, tense with anticipation, and psychologically complex.

Originally intended for Florence Cathedral, the statue was instead placed in the Piazza della Signoria as a symbol of the city’s republican ideals. David’s gaze, directed toward Rome, served as a defiant statement of Florentine independence. The statue remains one of the most celebrated works in Western art.

The Sistine Chapel: Ceiling of the Divine

In 1508, Michelangelo was commissioned by Pope Julius II to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican. Though he considered himself primarily a sculptor and was initially reluctant to accept the task, Michelangelo eventually took it on—and transformed the world of art forever.

Over four years, from 1508 to 1512, he painted more than 5,000 square feet of ceiling frescoes. The central panels depict scenes from Genesis, including the iconic “Creation of Adam,” where God and man nearly touch fingers. The complexity, dynamism, and spiritual intensity of the work set a new standard for artistic achievement.

Michelangelo painted most of the ceiling alone, standing on scaffolding and working in difficult conditions. The result was a triumph that redefined both the artist’s legacy and the very concept of visual storytelling.

The Dome of St. Peter’s

In his later years, Michelangelo turned increasingly to architecture. His most significant contribution in this field was his work on St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican. Appointed chief architect in 1546, Michelangelo redesigned much of the building and created the majestic dome that crowns it today.

Inspired by classical Roman architecture and the work of predecessors like Bramante, Michelangelo’s dome remains one of the most iconic features of the Roman skyline. His architectural work emphasized harmony, proportion, and spiritual symbolism, blending form with divine function.

The Last Judgment and Later Works

In 1534, Michelangelo began work on “The Last Judgment,” a massive fresco covering the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel. Commissioned by Pope Clement VII and later completed under Pope Paul III, the painting took five years to complete. It depicts the Second Coming of Christ and the final judgment of souls, featuring over 300 figures in dynamic and often contorted poses.

The work received both praise and criticism. Some admired its emotional intensity and complexity, while others were disturbed by its graphic depictions of nudity and torment. Despite the controversy, “The Last Judgment” solidified Michelangelo’s reputation as a visionary artist unafraid to confront the most profound themes of human existence.

In his final years, Michelangelo continued to work, producing architectural designs, poetry, and smaller sculptures like the “Rondanini Pietà,” which he worked on until just days before his death. His late style is marked by a growing spiritual intensity and introspection.

A Man of Passion and Solitude

Despite his fame, Michelangelo led a life marked by solitude and intense personal discipline. He never married and had no known children. His letters and poetry reveal a man who was deeply religious, often tormented by guilt and existential doubt, but also capable of profound love and sensitivity.

Michelangelo formed close relationships with several individuals, including the noblewoman Vittoria Colonna and the young aristocrat Tommaso dei Cavalieri. The nature of these relationships—particularly with Cavalieri—has been the subject of much scholarly debate, with some suggesting they were romantic.

His poetry, numbering over 300 sonnets and madrigals, adds another layer to his artistic genius. These works explore themes of beauty, mortality, and divine inspiration, offering a rare glimpse into the inner life of the Renaissance master.

Immortality Through Art

Michelangelo died on February 18, 1564, in Rome at the age of 88. He was buried in the Basilica of Santa Croce in Florence, fulfilling his wish to rest in his beloved homeland. His death marked the end of an era, but his influence had only just begun.

Few artists in history have matched Michelangelo’s range, depth, and impact. His sculptures continue to be studied for their anatomical precision, his paintings for their narrative power, and his architecture for its innovation. Artists from Caravaggio to Rodin, from Bernini to Picasso, have drawn inspiration from his work.

Today, Michelangelo is universally regarded as one of the greatest artists of all time—a divine genius whose work transcends its era and continues to speak to the human condition.