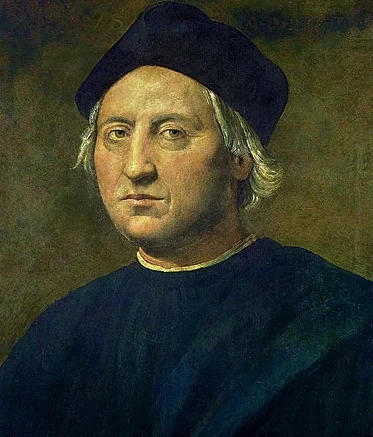

Christopher Columbus

There have been few more controversial figures in history than the man we know as Christopher Columbus, even though he was not born with that name. He is recognized as the “discoverer of America”, even though he knew nothing about it and it was not exactly discovered by him. His true identity, place of birth, aristocratic or plebeian origins, level of education, adventures in his youth, ambition or meanness, real knowledge or lucky fantasy are all topics of discussion and debate among biographers and historians.

As for him, the works collected in the Raccolta Colombiana (Italy, 1892–1896), the Documento Aseretto (discovered a few years later), the studies by the Spanish scholars Muñoz and Fernández Navarrete, and more recently the Diplomatorio Colombino, all clearly explain his humble Genoese origins and allow us to reconstruct his eventful and passionate biography without any doubt or omission.

As for the importance of his feat, it should be noted that his feat was surprising from a geographical point of view, very timely from a political point of view, but not as novel as is often claimed from a scientific point of view. Science at the end of the 15th century already recognized that the Earth was a sphere, knew that it was theoretically possible to sail west to reach the other side of the world, knew of the existence of the northern islands and lands explored by the Vikings and Danes, and believed that anyone attempting to sail west to reach India was likely to stumble upon some “unknown territory”.

Since the Middle Ages, there have been speculations and legends about the borders of the Dark Sea. The Irishman Saint Brendan mentioned a huge continent and “a huge island with seven cities”, and similar stories can be found in Gaelic, Celtic and Icelandic traditions. The Arabs in the Iberian Peninsula mentioned the Maghrebi explorers who set off from Lisbon and “sailed west for 11 days and then south for 24 days” before reaching a land where the sheep ate human flesh.

As early as the 14th century, the Venetian Niccolò Zenone drew a map that clearly marked the coastline of Greenland as well as Newfoundland and Nova Scotia. And a few years earlier, Cardinal Pierre d’Ailly had fully elaborated the idea of reaching the Great Khanate (described by Marco Polo) via a relatively short voyage westward in his book World Image. Columbus himself was convinced that he would find the mainland “about seven hundred leagues beyond the Canary Islands”.

This project was not new, and in fact it was even popular with cartographers and navigators as an alternative to the spice route. One of Columbus’s greatest fears was therefore that someone would cross the Atlantic before him. But neither he nor the scholars and sailors of the time could have imagined the immensity of the unknown continent or the immensity of the Pacific Ocean. On that day in 1492, a real scientific discovery began: not only did a new world appear, but the old earth also nearly doubled in size.

A young adventurer

Comparative research into various documents has enabled us to establish that the future navigator was born in Genoa between August 25 and October 31, 1451. His name was Christopher, after the first-born son of Domenico Colombo and Susanna Fontanarosa, born some five years earlier. The Colombo family had been settled in Liguria for at least a century, but its members had always been farmers or artisans with no wealth. Domenico himself seems to have moved from Quinto to Genoa around 1429 to learn the textile trade. The Colombo family also had three sons and a daughter, Bianchinetta. Two of the Colombo brothers were to play an important and continuing role in the adventures and misfortunes of their eldest sons Bartolomeo and Giacomo. The second of these was known as Diego in Spain.

Cristóforo was too young to help his father with the cheese-making and inn-keeping, or to accompany him on business trips to Quinto or Savona. He was a bright and active boy, but there is no record of him receiving any kind of education. What really fascinated him were the port, the stories of the sailors and the ships from faraway lands. Genoa was an important maritime trading center, and it was not difficult for the young Christopher Columbus to find opportunities to board the ships of the city’s large shipping companies, which operated a variety of merchant shipping routes across the Mediterranean. As a result, he was able to practice on deck and learn about navigation. He asked the captains about wind and currents, read sea charts, and practiced using navigation instruments. By the time he was 20, he had already become an excellent crew member.

In 1476, Christopher may have participated in a Ligurian naval expedition to the Greek island of Chios (a Genoese possession), after which he traveled to Flanders on a merchant convoy. But shortly after crossing the Strait of Gibraltar, an accident changed the young Columbus’s fate. At that time, the Portuguese and French were supporting Juana la Beltraneja’s claim to the throne of Castile, and French warships attacked the Genoese fleet, on the mere grounds of piracy.

His ship sank and Christopher swam to the Portuguese coast. Shortly afterwards, he arrived in Lisbon and worked for the important shipping company Centurione, which was the owner of the attacked fleet. There, he changed his name to Cristóvão and his surname to Colom or Colón. His brother Bartolomé also joined him, who was also a sailor and interested in cartography.

The older Colomos was in the habit of going to mass at the monastery of Santos. There he fell in love with one of the nuns, Filipa Môniz Palheiro, a beautiful young woman from a noble family. Her mother Isabel Moniz was of noble birth and related to the House of Braganza, while her father Diego Palestrello was also a Genoese who was closely involved in the maritime affairs of the Portuguese royal family and was at that time the governor of the island of Porto Santo in Madeira. In 1477, Christopher proposed to Felipa and won her heart. A year later they had a son, whom they named Diego.

Under the influence of his father-in-law, Columbus became increasingly interested in the geographical and scientific aspects of navigation, rather than purely commercial aspects. This was probably also influenced by the early death of his wife (Felipa died a year after giving birth) and his falling out with the Centurione family, with whom he was engaged in a long legal battle, partly reflected in the Documento Aseretto.

The great project

From that moment on, Christopher Columbus began to dream and design this ambitious and far-sighted project that would obsess him for the rest of his life: to sail west and explore a shorter, safer route to the Indies. It has been said that this theoretical idea was very popular at the time, and that more or less legendary precedents were cited. To this we must add the inspiration that the navigator himself may have drawn during his stay in the port of Sanlúcar, as well as the atmosphere of “sea expansion” that Portugal was experiencing from the discoveries and explorations of the Atlantic islands and the African coast.

But the trigger could have been the letter from the Florentine scholar Paolo d’Arpozzo Toscanelli to the Lusitanian cleric Fernando Martins, in which he expressed the hope that the Portuguese king would be interested in his ideas. This document (or a copy) may have reached Christopher Columbus via the mediation of Diego Palácio. The Florentine humanist’s theory summarized the current understanding of the shape of the earth, which was that it was spherical, but the calculation was wrong and only 125 degrees were calculated for the distance between the Canary Islands and Asia.

Christopher Columbus accepted this idea, translated it into an expedition plan and took it to King John II of Portugal. The monarch stipulated that the expedition should not set sail from the Canary Islands, as if the voyage was successful, the Castilian crown could claim the lands conquered under the Treaty of Alcáçovas. Columbus, who believed only in his calculations from the Canary Islands, considered setting sail from Madeira too risky, and no agreement was reached. Some say that the monarchs, who were suspicious of the foreigner with no qualifications or education, secretly sent another expedition, which ultimately failed. Christopher was unhappy about this deception, and probably also because of financial difficulties and the hope of finding another protector, he left Lisbon with his son Diego and his brother Bartholomew. They sailed around the peninsula with the intention of leaving young Diego in the care of his aunt Violante Moniz, who lived in Huelva.

On the way, they stopped at the nearby Franciscan convent of La Vid, where they stayed as guests. The guardian, Friar Juan Pérez, who had been the queen’s confessor, was very interested in the plans of the foreigner who called himself Colón (XR is the Christian alphabet) and got his learned colleague, Friar Antonio de Marchena, an expert in astronomy and cosmography, interested in him. Both friars recommended him to the Duke of Medina-Sidonia, who was very interested and kept Columbus for more than a year to prepare the expedition. However, the Catholic Monarchs did not allow the project to go ahead, and the Duke was only able to send the navigator to their court in Córdoba.

In 1486, a think tank in Salamanca again advised against the venture, perhaps because they had already obtained evidence of how long and arduous the voyage would be. But Catholic Queen Isabella, despite being deeply involved in the war for Granada, did not completely give up on the idea of bringing the Castilian flag to India; she granted the navigator a pension and implored him to stay in Córdoba. Christopher settled in an inn and fell in love with Beatriz Enríquez, a young woman 20 years his junior. In 1488, the couple had a son, Hernando Colón, who would become the admiral’s first biographer and the main person responsible for the secrecy and ambiguity that surrounded his figure for centuries.

After conquering Granada, the Catholic Monarchs received Columbus in the best of moods. But the foreigner’s demands were excessive: a naval department in the Ocean Sea, hereditary viceroyalty over the lands he discovered, and the lion’s share of the wealth acquired by him or his men through conquest or trade. Catholic Monarch Fernando

The monks at the monastery of La Rabida managed to dissuade him, and with the help of courtiers Luis de Santangel and Juan de Coloma, they persuaded the Catholic monarchs to agree to the so-called Santa Fe Protocol, which in 1492 granted the admiral the titles and privileges he sought, albeit only 10% of the potential profits. But the depleted royal coffers did not allocate a single penny to finance the expedition; despite the legend, the queen’s jewels had been mortgaged to moneylenders in Valencia. Santangel, who was connected to them, was the one who came up with the brilliant idea of mortgaging the Genoese’s lease on the port of Valencia, which was accepted by the wealthy Ligurian banker Juan de Bellardi through the mediation of Christopher Columbus himself. Once the financial problems were solved, all that remained was to find the ships and crew.

Discovery of America

Columbus faced another stroke of providence: Martín Alonso Pinzón, a wealthy shipowner, old seafarer and wealthy merchant from Huelva, was fascinated by Columbus’s plans. Thanks to Pinzón’s authority, the dubious sailors from Huelva agreed to join this strange adventure, and the shipowners Pinto and Niño agreed to give up the two yachts that bore their names. Martín Alonso and his brother Vicente Yáñez Pinzón were to take charge of the two ships, while the admiral chose a Cantabrian caravel moored in the port of Palos called Marigalante. The owner of this ship, the cartographer Juan de la Cosa, offered to join the expedition as captain, and the flagship was renamed Santa Maria. All that remained was to procure equipment and provisions. The Pinzon brothers and their friends raised the remaining funds, and everything was ready for the voyage to begin.

Despite the resistance of Martin Alonso and the doubts of Juan de la Cosa, Columbus insisted on following the route marked out at latitude 28°, which passed by the island of El Hierro. Fortunately, thanks to an intuition or knowledge that the admiral did not divulge, this route proved to be very conducive to a carefree westward progress. The small fleet entered the mysterious “Black Sea”.

But after more than two months, no land was in sight, and an attempted mutiny was quashed by the unassailable authority of Hirayama. It was the old pilot who finally persuaded Christopher Columbus to change course and sail southwest. Soon they began to see drifting tree branches, birds and other unmistakable signs that they were approaching the coast. It must be noted that if they had sailed along the 28th parallel, they would have reached Florida, and perhaps the story of the discovery of America and the New World would have been different.

During the night of October 11th to 12th, 1492, the sailor Juan Rodríguez de la Palma (nicknamed El Triana) shouted “Earth!” from the crow’s nest of the La Pinta. At dawn, they landed on an island (either Guanahaní or Watling Island in the Bahamas), which Columbus named San Salvador. After establishing that the island belonged to the Great Khan, the navigator set out to find riches in the archipelago. But all he found were tropical forests and naked natives.

Columbus decided to use the wreckage to build a temporary fort, which he named La Navidad (The Nativity), as his birthday was on December 25. On January 4, 1493, Columbus stayed behind with a few volunteers, while the rest of the men set sail for home. The captain of the La Nina, Admiral Vicente Pinzon, ordered him to sail north – the wrong course, as it turned out. But he was right again: the Gulf Stream carried him safely to the peninsula, while Martin Alonso Pinzon’s Pinta was blown off course by the storm. One arrived in Lisbon, the other in Bayonne (Galicia). Although Columbus had rejected the offer by John II of Portugal to claim his discoveries for himself, the seriously ill Martin Alonso Pinzon died soon afterwards.

The Catholic Monarchs welcomed Christopher Columbus to Barcelona in a grand ceremony and did not succumb to the plots against him. They confirmed his titles and privileges and added a castle and a lion to his coat of arms by royal decree. But the admiral was only thinking of returning to India – and this time with a much stronger naval force.