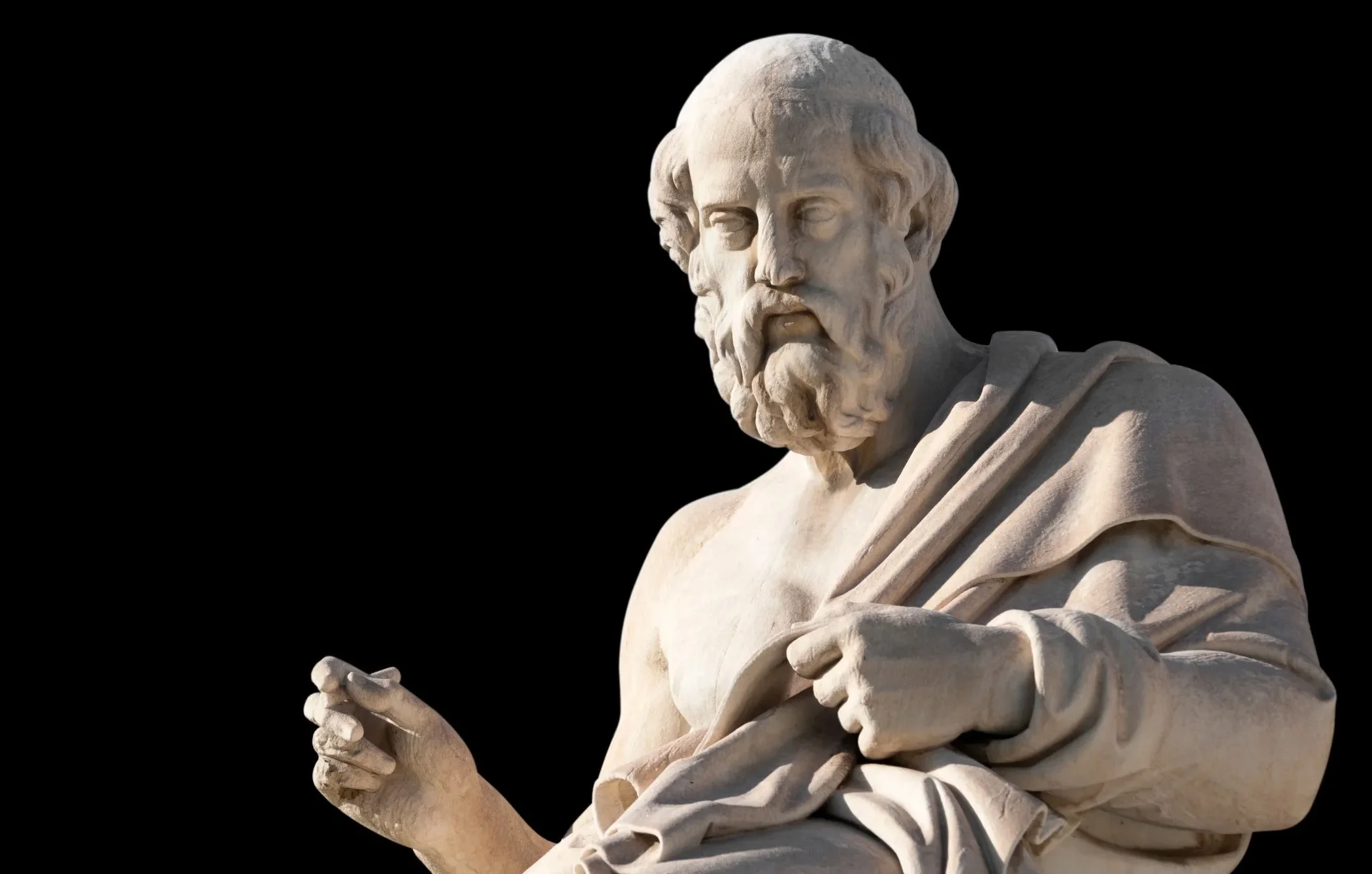

Plato: Learn the biography of the disciple of Socrates and teacher of Aristotle.

(Athens, 427 – 347 BC) Greek philosopher. Plato is the central figure of the three great thinkers on whom the entire European philosophical tradition is based. Along with his teacher Socrates and his disciple Aristotle, he is one of the most important philosophers in history. The British philosopher Alfred North Whitehead emphasised its importance when he stated that Western thought is nothing more than a series of footnotes to Plato’s dialogues.

Socrates left no written work, and Aristotle’s system was in many ways opposed to that of his teacher. This makes the boldness of the statement seem justified. Plato’s work is undeniably radical in its logical and literary elaboration. It established a series of constants and problems that marked Western thought beyond its immediate influence. This would be felt both among the pagans (the Neoplatonism of Plotinus) and in Christian theology, which was largely based on Platonic philosophy by St. Augustine.

Born into an aristocratic family, Plato abandoned his initial political vocation and literary pursuits for philosophy, attracted by Socrates: he was his disciple from the age of twenty and openly confronted the Sophists (Protagoras, Gorgias). After Socrates’ death in 399 BC, he fled Athens and withdrew from public life. However, political issues always occupied a central place in his thinking, and he went on to conceive an ideal model of the state.

He travelled extensively throughout the East and southern Italy, where he encountered the disciples of Pythagoras. However, his time as an advisor to the court of King Dionysius I the Elder in Syracuse was negative, and he was even a prisoner of pirates for a period of time. In 387, he founded a school of philosophy on the outskirts of the city, next to the garden dedicated to the hero Academus, from which the name “Academy” derives. Plato’s Academy was a kind of sect of wise men organised with its own rules. It had a student residence, library, classrooms, and specialised seminars. It was the precedent and model for modern university institutions.

Philosophy encompassed all knowledge and all subjects were studied and researched there. Then, as different branches of knowledge emerged, such as logic, ethics, and physics, they were given their own specialised disciplines. It survived for more than nine hundred years – until Justinian ordered it closed in 529 AD – and educated figures as important as his disciple Aristotle.

Works of Plato

Socrates didn’t leave any written work, but Plato’s has been almost completely preserved. Most are written in dialogue form, and Plato was the first author to use dialogue to expound philosophical thought. This form was in itself a new cultural element, with the contrast between different points of view and the psychological characterisation of the interlocutors indicating a new culture. In this culture, there was no longer room for poetic or oracular expression, but rather for debate to establish knowledge whose legitimacy lay in the free exchange of points of view and not in simple enunciation.

The twenty-six Platonic dialogues that have survived are authentic, and can be divided into three groups. The dialogues of the Socratic period (396-388), including the Apology, Crito, Euthyphro, Laches, Charmides, Ion, the Hippias Minor and perhaps Lysis (which may be later), clearly reveal the influence of Socrates’ methods and are distinguished by the predominance of the mimetic-dramatic element: they begin abruptly, without preparatory preambles. All of these works predate Plato’s first trip to Sicily, and they are dominated by Socratic-style investigative dialogues.

The following dialogues belong to a transitional phase among the constructive or systematic dialogues of the following period: Protagoras, Meno (which announced the doctrine of Ideas), Gorgias, Menexenus, Cratylus, and Euthydemus. The great dialogues of this stage are the Phaedo, whose theme is the immortality of the soul; the Symposium, in which six speakers debate love; the Republic, Plato’s most systematic text, the fruit of many years of work, which presents three main lines of argument (ethical-political, aesthetic-mystical, and metaphysical) combined into a whole; and the Phaedrus, which, in the form of a dramatic dialogue, discusses aspects of beauty and love and contains moments of profound poetry. These dialogues are indisputably Plato’s expressive peak. They are not mere philosophical essays, but literary works dealing with philosophical themes. As such, they are not limited to a single theme or subject.

The dialogues of the late or revisionist period were written after the founding of the Academy. While they may lack the dramatic and literary merits of the earlier dialogues, they display greater subtlety and maturity of judgment, as they more closely resemble the thinker determined to present the definitive exposition of his philosophical thought than the artist. In Parmenides, Plato boldly revises the doctrine of Ideas; in Theaetetus, he directly confronts Protagoras’ skepticism about knowledge, while extolling the contemplative life of the philosopher; in Timaeus, he confidently expounds the myth of the creation of the world by the Demiurge; in Philebus, he discusses the relationship between the Good and pleasure, and in The Laws he attempts to adapt his doctrine of the ideal state more to reality, taking as his reference the constitutions and laws of various Greek cities.

Plato’s style is marked by a combination of thought and expression that is admirable. He uses myth to make philosophical thought more evident. The most famous of these is the myth of the cave used in The Republic, but the myths of the afterlife (Gorgias) and Epimetheus (Protagoras) are also well known.

The following essay will explore the philosophical ideas of Plato.

Plato’s extensive corpus, which spans a period of over fifty years, has enabled the formulation of a reasonably reliable opinion regarding the evolution of his thought. From his early works devoted to moral inquiry (following the Socratic method) or to defending the memory of Socrates, Plato went on to develop his philosophical and political ideas in constructive or systematic dialogues, and then to revise and complete his own theories in the difficult works of his final period.

The content of these writings is metaphysical speculation, but with a clear practical orientation. Two themes emerge as the most prevalent. On the one hand, knowledge can be defined as the study of the nature of knowledge and the conditions that make it possible. Furthermore, the concept of morality is of fundamental importance in practical life and in the realisation of the human aspiration to happiness. This is true in both the individual and collective sense, as well as in the ethical and political sense. The aforementioned issues are resolved in a philosophical system of great ethical scope based on the theory of Ideas.

The Theory of Ideas

The doctrine of Ideas is predicated on the assumption that, in addition to the world of physical objects, there exists what Plato calls the intelligible world (cósmos noetós). The world is posited as a spiritual realm comprising a plurality of ideas, including the concepts of Beauty and Justice. Ideas are regarded as perfect, eternal, and immutable; they are also considered to be immaterial, simple, and indivisible.

The world of Ideas is characterised by a hierarchical order, with the concept of the Good occupying the pinnacle of the hierarchy. This notion of the Good serves as a beacon, illuminating and communicating its perfection and reality to the Ideas that reside beneath it in the hierarchical structure. In the subsequent tiers of this hierarchy, albeit with occasional hesitation in his articulation, Plato introduces the concepts of Justice, Beauty, Being, and the One. Subsequently, there are those that express polar elements, such as “identical-different” or “movement-rest”. Following these are the ideas of “numbers” or mathematics, and finally, those of the beings that make up the material world.

The world of Ideas, apprehensible only by the mind, is eternal and immutable. Each concept in the intelligible realm serves as the archetype for a distinct category of entities in the sensible universe (cósmos aiszetós), that is, the universe or material world in which we reside, comprising a plurality of beings whose characteristics are antithetical to those of Ideas: they are mutable, imperfect, and perishable. The intelligible world is home to ideas such as Stone, Tree, Color, Beauty, and Justice; and the things of the sensible world are only imitations (mimesis) or participations (mézexis) of such ideas, that is, imperfect copies of these perfect ideas.

In his work The Republic, Plato illustrated this conception with the well-known myth of the cave. Plato’s hypothetical scenario involves a group of individuals who have been confined in a cave since birth, never having experienced the sight of sunlight. Their visual perception is limited to shadows cast by a fire on a wall, as well as the statues and various objects carried by porters passing behind them. For these men, the shadows (the beings of the sensible world) constitute the only reality; however, if they were to be freed, they would realise that what they believed to be real were mere shadows of the true things (the Ideas of the intelligible world).

It is the contention of this paper that the intelligible world is the sole manifestation of truth and reality; the sensible world is merely an appearance of being. The physical world, as perceived through the senses, is subject to constant change and degeneration. Consequently, the knowledge derived from this physical world is limited and inconstant. It is a world of appearances that can only engender opinion (doxa), the value of which is dependent on its foundation, but which is always worthless. True knowledge (episteme) is defined as the knowledge of Ideas. At this juncture, the influence of the esteemed Parmenides becomes evident.

In the Timaeus, Plato expounds the genesis of the perceivable universe through the conceptualisation of a formidable originator, the Demiurge, a transcendent deity who, in the perpetual contemplation of Ideas, aspires, from a state of intrinsic benevolence, to disseminate maximal beneficence throughout matter. The Demiurge, having created empty space and initiated the process from chaotic and eternal matter, modelled regular polyhedra from the four elements (earth, fire, air, and water, according to the formulation of Empedocles), and, through the combination of these elements, formed the different beings of the sensible world, taking the Ideas as models. It is evident that these beings could not be perfect due to the limitations of the nature of matter. It is imperative to emphasise that the Demiurge, originating from matter, has created material entities; the human soul, which is immaterial, does not constitute his creation.

The soul is the seat of the personality and the seat of moral sense.

It is therefore posited that there is an intelligible world, that of Ideas, which engenders knowledge, and a sensible world, that of our own experience. This duality is also present in human beings. The human entity is constituted by two distinct realities that have coincidentally coalesced: the mortal body, which is associated with the physical world, and the immortal soul, which is intrinsic to the realm of Ideas, with which it was previously engaged prior to its union with the body. The human body, composed of material matter, is inherently imperfect and subject to change; in essence, it is comparable to all physical entities in its imperfect state. Indeed, the profound disparity between the null value of the body and the exalted value of the soul compels Plato to assert in the Alcibiades that “man is his soul.”

In contradistinction to the coarse materiality of the body, the soul is spiritual, uncomplicated, and indivisible. This fundamental principle underlies the concept of the eternal and immortal nature of matter, as the process of destruction or death of an entity is predicated on the disintegration of its constituent components. The multifarious functions of the soul are said to converge in its three aspects: the rational soul (logos) is located in the brain and endows man with his intellectual faculties; the passionate or irascible soul (zimos), located in the chest, is responsible for passions and feelings; and the concupiscent soul (epizimia), located in the belly, is the source of base instincts and purely animal desires.

Plato elucidated the origin of the soul through the myth of the winged chariot, as outlined in the Phaedo. The postulation posits that the soul inhabits a celestial realm, wherein it is believed to exist in a state of perpetual felicity, engaged in profound contemplation of abstract ideations. This metaphysical concept is further elaborated through the depiction of a celestial procession, wherein each soul is delineated as being borne aloft on a chariot, guided by a charioteer and towed by a pair of mythical, winged horses, one of pristine white and the other of sinister black. At a certain point, the black horse bolts, the chariot veers off the road, and the soul falls into the sensible world. In summary, the hypothesis is that souls became incarnated in bodies in the sensible world due to a fault in their concupiscent aspect (the black horse; the white horse represents the passionate or irascible aspect), which reason (the charioteer) was unable to prevent.

The soul, therefore, finds itself incarnated in the body because of a fault committed; hence the body is like a prison for the soul. The union of soul and body is accidental, with the soul’s natural place being the world of Ideas, resulting in a state of discomfort. The soul is likened to a rider on a horse or a pilot on a ship, in that it must govern the body accordingly. Nevertheless, its aspiration is to liberate itself from the body, and to achieve this objective it must apply itself to the process of purifying itself. Souls that achieve such purification will return to the world of Ideas after the death of the body; those that do not will go to the infernal region of Hades, where, after a period of torment (specific to each soul according to the faults committed), they will be allowed to choose a new body in which to be reincarnated.

The subjects of ethics and politics are the focus of this text.

The pursuit of happiness, as espoused by the aforementioned theorist, is predicated on the continuous exercise of virtue, which is posited as a means of perfecting and purifying the soul. In the Phaedo, he wrote that “purification of the soul is achieved through the separation of the soul from the body as much as possible.” Through the mastery of the passions that bind the soul to the body and the sensible world, the soul achieves a detachment from the earthly realm and approaches rational knowledge. This process continues until the soul is inflamed with a love for Ideas, at which point it attains complete purification. This profound affinity for ideas constitutes the fundamental essence of Platonic love, a concept that diverges significantly from its subsequent interpretation within literary tradition and its contemporary manifestation.

The practice of virtue is fundamentally the practice of justice (dikaiosíne), a harmonious compendium of the three particular virtues that correspond to the three components of the soul: wisdom (sofía) is the virtue of reason; fortitude (andreía) of the will must modulate the passionate or irascible soul toward noble affections; and temperance (sofrosíne) must prevail over the appetites of the concupiscent soul. In the philosophy of Plato, the concept of wisdom is defined as the ability to establish a connection with Ideas through the acquisition of knowledge. This intellectual process, as opposed to one that is sensorial in nature, enables the soul to recall the world of Ideas from which it originates.

However, the complete realisation of this human ideal can only occur in the social life of the political community, where the state provides harmony and consistency to individual virtues. Plato’s ideal state would be a republic comprising three classes of citizens (the people, the warriors, and the philosophers), each with its specific mission and characteristic virtues, corresponding to the aspects of the human soul: philosophers would be called upon to govern the community, because they possess the virtue of wisdom; warriors would ensure order and defence, relying on the virtue of strength; and the people would work in productive activities, cultivating temperance. Consequently, the virtue of justice could come to characterise society as a whole.

The two upper classes would reside in a communal regime, in which all property, children and women would be state-owned, thus leaving institutions such as the family and private property to the general populace. The hypothesis is that by divesting the ruling classes of these institutions, their corruption would be avoided, since they would neither be able nor need to accumulate wealth, nor would they have relatives to favour. This scheme, along with other aspects of his ideas, underwent a period of revision in The Laws, a work written in his old age which saw the dissolution of these restrictions. The state would assume responsibility for the sphere of education and the selection of individuals (on the basis of their abilities and virtues) for assignment to each class. The concept of collective justice is predicated on the notion that each individual is fully integrated into their role, with their interests being subordinated to those of the state.

Furthermore, he theorized about the different forms of government, which, according to Plato, follow each other in a cyclical order in which each system is worse than the previous one. For the philosopher, monarchy or aristocracy (government by a single exceptionally gifted individual or a wise and virtuous minority, who aspire only to the common good) is considered to be the optimal form of government. The transition from monarchy to timocracy occurs when the military class, rather than fulfilling its role of safeguarding society, utilises force to amass power. In the context of an oligarchy, the rule of a wealthy minority over an impoverished populace is a common occurrence. The concept of democracy, or rule by the people, is predicated on the notion that the most competent individuals will emerge as leaders, thereby ensuring the optimal functioning of society. However, Plato’s perspective on this notion is rather negative, as he believes that those who are least skilled are often elected to positions of authority, resulting in a state of anarchy. Finally, tyranny, led by a demagogue who suppresses all freedom, restores order; it is the worst form of government.

Plato endeavoured to implement his philosophical concepts through his agreement to act as tutor and advisor to Dionysius II of Syracuse, the son of Dionysius I the Elder. This undertaking followed Plato’s unsuccessful counsel to Dionysius I, prior to the establishment of the Academy. The experiment was unsuccessful on two occasions (367 and 361 BC) due to the clash between the philosopher’s idealistic thinking and the harsh reality of politics.

The influence of the subject

However, the influence of Plato’s ideas, whether directly or through his student Aristotle, persisted throughout the subsequent history of the Western world. Notable aspects of Plato’s philosophy, such as his dualistic conception of the world and human beings (matter-spirit, body-soul), the notion of rational knowledge as superior to sensory knowledge, and the societal division into three functional orders, served as recurring themes in European thought for centuries.

In the late antiquity period, the philosophical school of thought known as Platonism underwent significant development and expansion, particularly through the contributions of the Neoplatonic school, which emerged in the 3rd century AD. Christianity, commencing with Augustine of Hippo (4th century), identified numerous points of affinity with Plato’s philosophies, such as a disdain for the material world and the primacy of the soul, which served as the foundation for its religious conceptualisations. Christian theology remained predominantly Augustinian until a significant reformation by Saint Thomas Aquinas (13th century), which integrated Aristotelian thought, thereby marking a pivotal shift in theological discourse. During the 15th and 16th centuries, the European Renaissance was characterised by a resurgence of interest in ancient philosophy, which subsequently led to a final resurgence of Platonism.